PHOTO ELYSEE

29.03 – 04.08.24

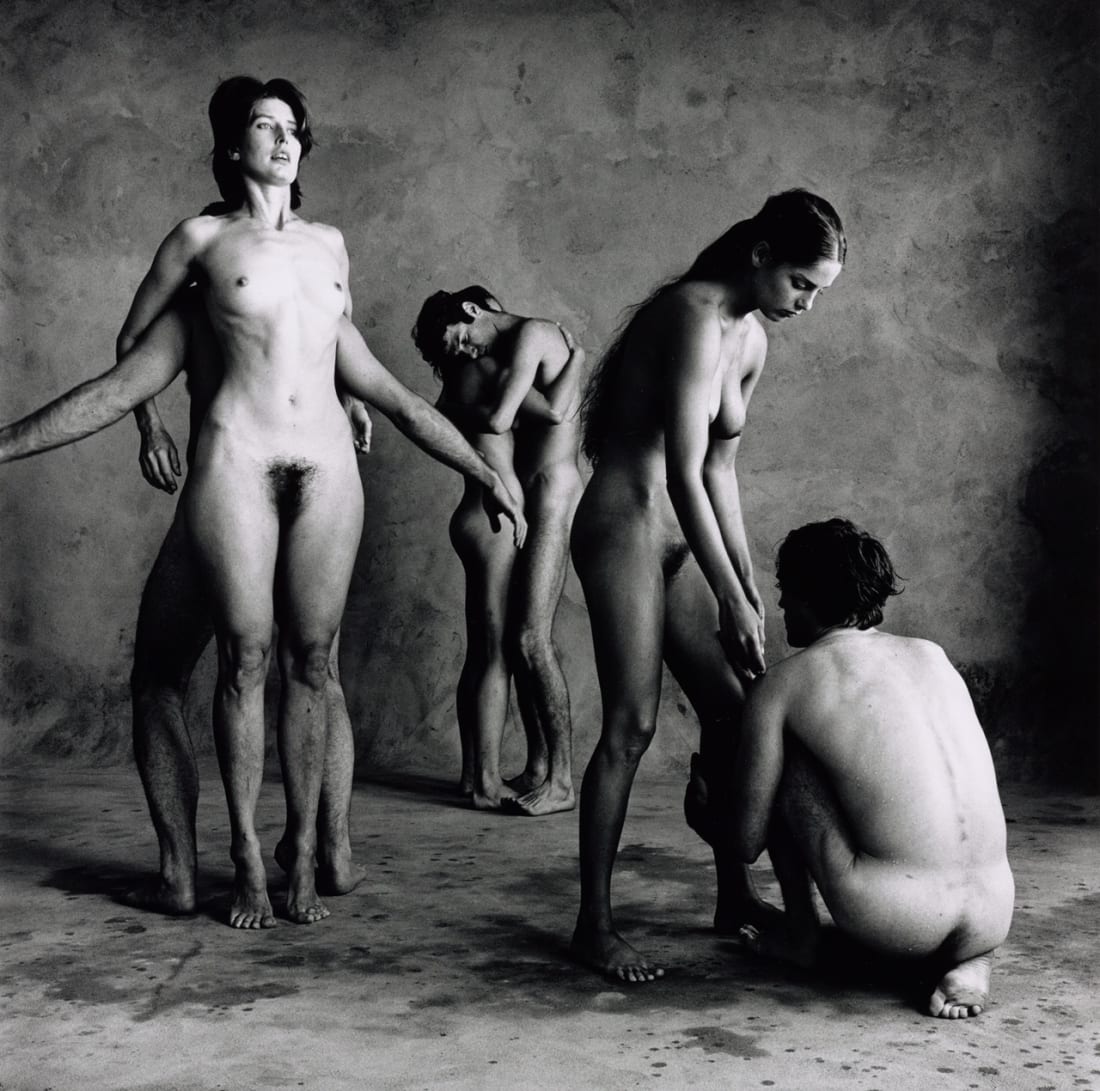

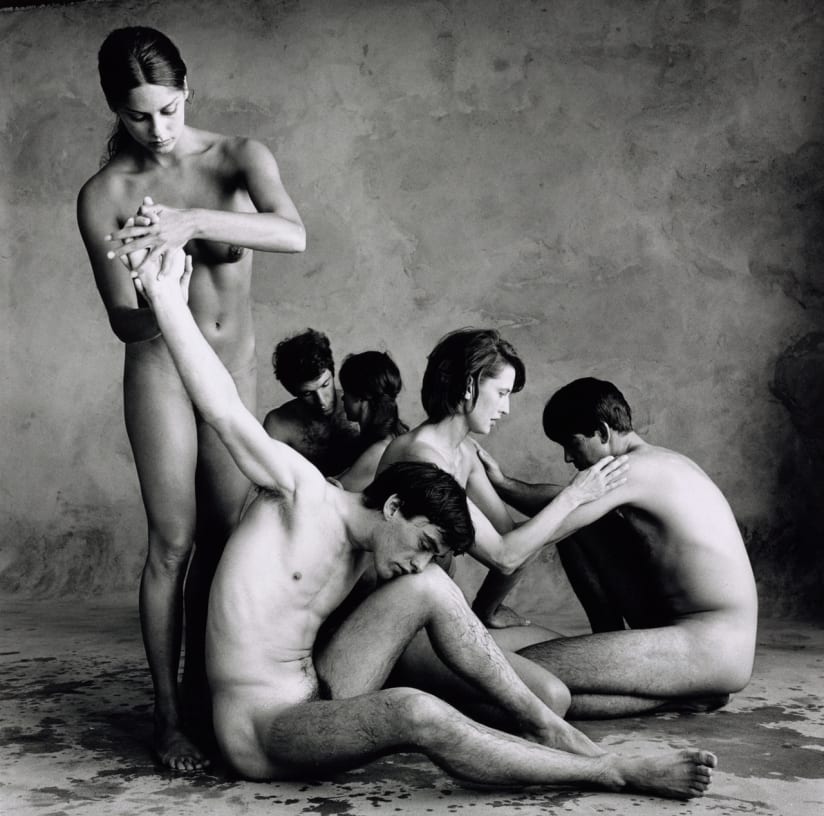

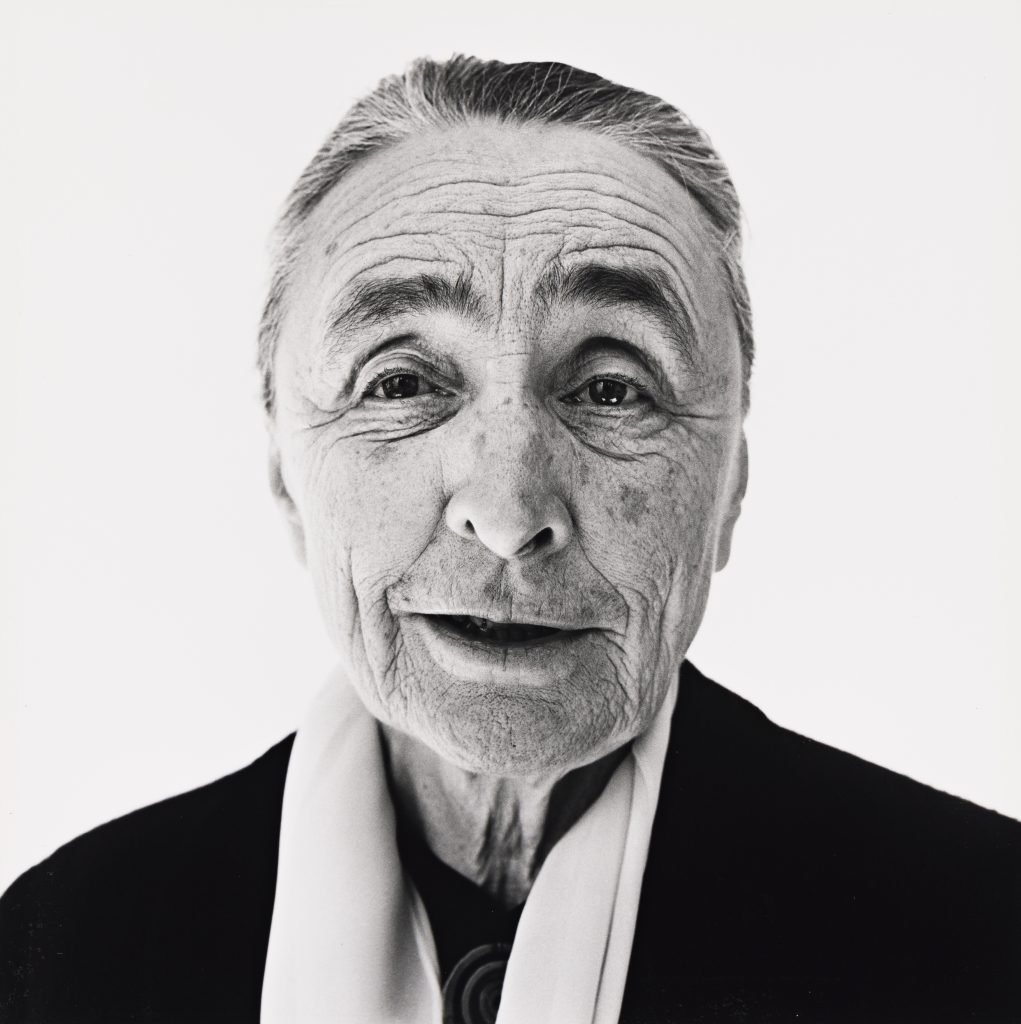

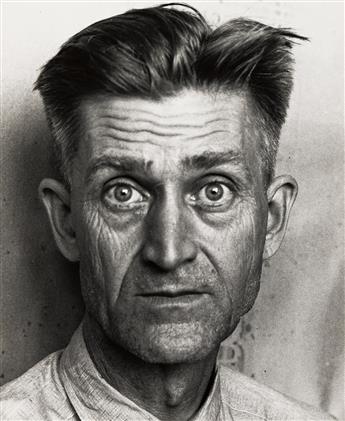

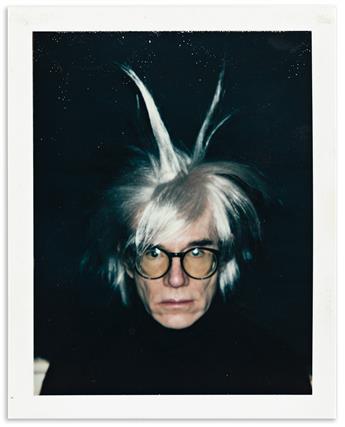

Cindy Shermanhas been exploring themes of representation and identity for over 40 years. Her portraits have established her as one of the most recognized and influential artists of our time. In the dual role of photographer and model, playing with makeup, wigs and costumes–traditional methods of transformation–Sherman creates portraits of women with similar yet very different features, always using her own body. The sense of fractured identity, characteristic of our contemporary society, is particularly emphasized in her figures, constructed since the 2000s using digital manipulations. In her most recent series, the malleability of the self-image is expressed in these face collages in which Sherman accentuates incongruous facial details. These women who express a variety of emotions are all composites of the artist's own face. Sherman is both behind and in front of the camera, viewer and object. This series shows how complex our identity is, how it is subject to multiple constructions, and how impossible it is to capture in a single image.

Cindy Sherman is considered to be one of the most important American artists of her generation. Her ground-breaking photographs have interrogated themes around representation and identity in contemporary media for over four decades. In this new body of work, the artist collages parts of her own face to construct the identities of various characters, using digital manipulation to accent the layered aspects and plasticity of the self. Sherman has removed any scenic backdrops or mise-en-scène–the focus of this series is the face. She combines a digital collaging technique using black and white and color photographs with other traditional modes of transformation, such as make-up, wigs and costumes, to create a series of unsettling characters who laugh, twist, squint and grimace in front of the camera.

To create the fractured characters, Sherman has photographed isolated parts of her body–her eyes, nose, lips, skin, hair, ears–which she cuts, pastes and stretches onto a foundational image, ultimately constructing, deconstructing and then reconstructing a new face. In the double role of both photographer and model, Sherman upends the usual dynamic between artist and subject. Here, the sitter does not technically exist–all portraits are comprised of composites of the artist’s face–however, they still read as classical portraiture and, despite the layers, the image still gives a true impression of a ‘sitter’.

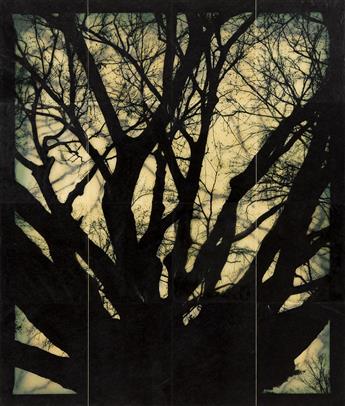

Tightly cropped, with frames full of hair, stretched-out faces or swathes of material, Sherman’s construction of her characters disrupts the voyeur-gaze and subjectobject binaries that are often associated with traditional portraiture. In works such as Untitled #661 (2023), subtle changes, such as the positioning of a towel, the copy and pasting of an eyebrow from one image to another, or the elongation of a facial feature, alter the entire demeanor and representation of the imagined ‘sitter.’

This type of warping of the face is akin to the use of prosthetics that Sherman began using in the mid1980s in series such as History Portraits (1988) or Masks from the 1990s, exploring the more grotesque or abject aspects of humanity. Like her use of costumes, wigs and makeup, the application of prosthetics would often be left exposed, breaking, rather than upholding, any sense of illusion. Similarly, the use of digital manipulation in her new series exaggerates the tensions between identity and artifice.

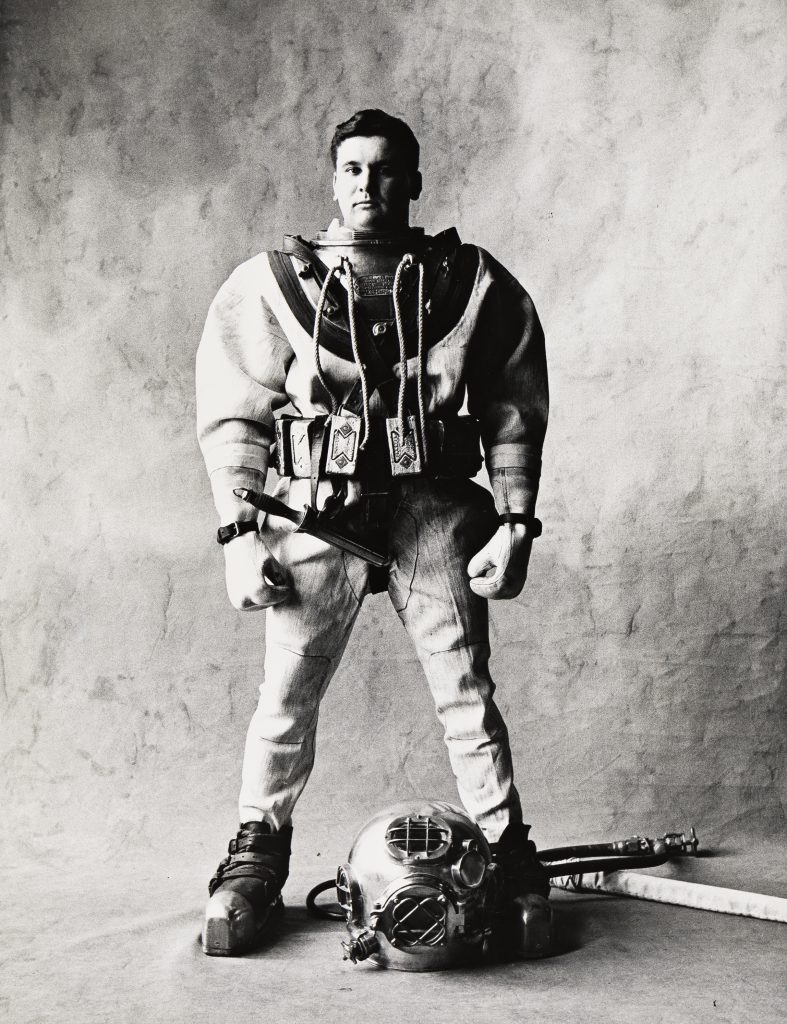

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #631, 2010/2023 © Cindy Sherman, Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

This is heightened in works such as Untitled #631 (2010/2023) where Sherman combines both black and white and colored fragments, highlighting the presence of the artist’s hand and disrupting any perception of reality, while also harking back to the hand-colored and hand-cut works that she made in the 1970s. By employing this layering technique, Sherman creates a site of multiplicity, exploring the notion that identity is a complex, and often constructed, human characteristic that is impossible to capture in a singular picture.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #627, 2010/2023 © Cindy Sherman, Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

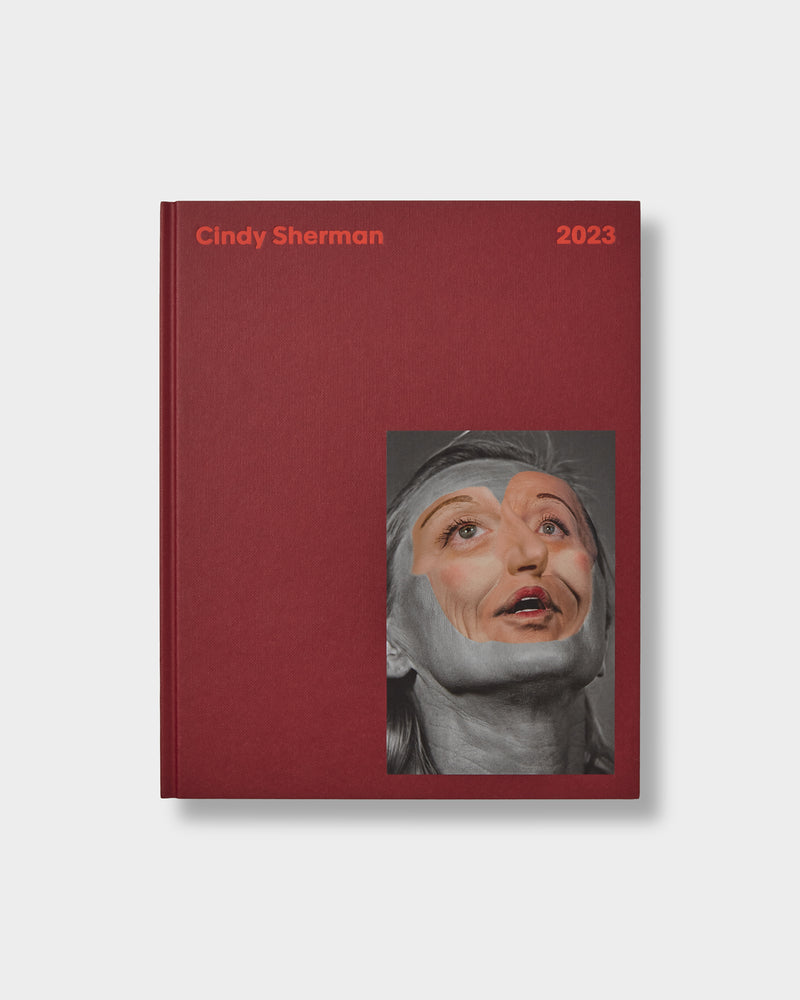

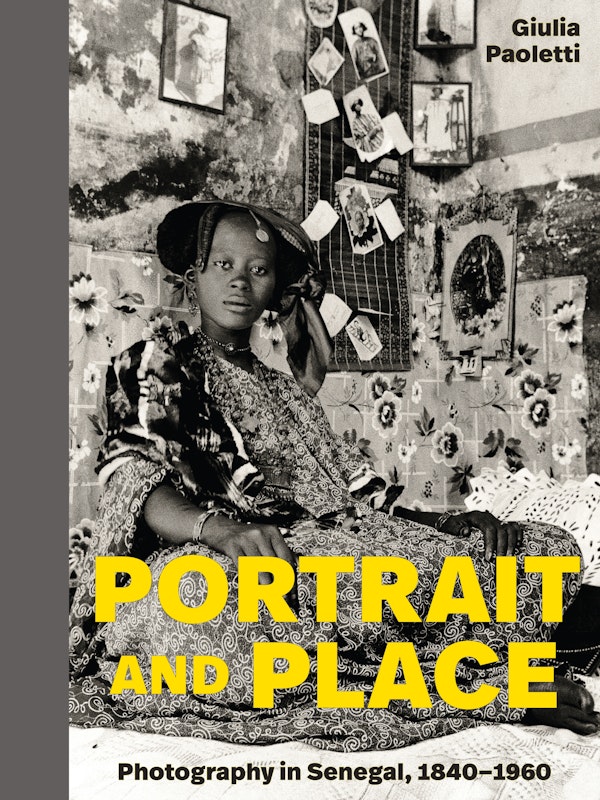

Catalogue

The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue by Hauser & Wirth Publishers.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Born in 1954, Cindy Sherman lives and works in New York. Coming to prominence in the late 1970s with the Pictures Generation group, Sherman first turned her attention to photography at Buffalo State College in the early 1970s. In 1977, shortly after moving to New York City, she began her critically acclaimed series of Untitled Film Stills. Sherman continued to channel and reconstruct familiar personas known to the collective psyche, often in unsettling ways, and by the mid to late 1980s, the artist’s visual language began to explore the more grotesque aspects of humanity through the lens of horror and the abject, as seen in works such as Fairy Tales (1985) and Disasters (1986-89). These highly visceral images saw the artist introduce visible prostheses and mannequins into her work, which would later be used in series such as Sex Pictures (1992) to add to the layers of artifice in her constructed female identities.

Like Sherman’s use of costumes, wigs and makeup, their application would often be left exposed. Her renowned History Portraits, begun in 1988, used these theatrical effects to break, rather than uphold, any sense of illusion. Since the early 2000s, Sherman has used digital technology to further manipulate her cast of characters in her work. This is evident in her Clown series (2003), Society Portraits (2008) and her Flappers series (2016).

In 2017, Sherman began using Instagram to upload portraits that utilize several face-altering apps, morphing the artist into a plethora of protagonists in kaleidoscopic settings. Disorientating and uncanny, the posts highlight the dissociative nature of Instagram from reality.

Sherman’s work has been recognized by numerous grants and awards, including a MacArthur Fellowship, Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship and the Hasselblad Award. It has also been the subject of several major retrospectives, including at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles in 1998, the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 2012, the National Portrait Gallery, London, in 2019, and at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris in 2023.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #659, 2023 © Cindy Sherman, Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth 9 PRESS IMAGES © Cindy Sherman, Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #648, 2023 © Cindy Sherman, Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth