Paul Strand (American, 1890–1976) was one of the greatest photographers in the history of the medium. It will explore the remarkable evolution of Strand’s work, from the breakthrough moment in the second decade of the twentieth century when he brought his art to the brink of abstraction to his broader vision of the place of photography in the modern world, which he would develop over the course of a career that spanned six decades.

Born in New York City, Strand first studied with the social documentary photographer Lewis Hine at New York’s Ethical Culture School from 1907–09, and subsequently became close to the pioneering photographer Alfred Stieglitz. Strand fused these powerful influences and explored the modernist possibilities of the camera more fully than any other photographer before 1920. In the 1920s, Strand tested the camera’s potential to exceed human vision, making intimate, detailed portraits, and recording the nuances of machine and natural forms. He also created portraits, landscapes, and architectural studies on various travels to the Southwest, Canada, and Mexico. The groups of pictures of these regions, in tandem with his documentary work as a filmmaker in the 1930s, convinced Strand that the medium’s great purpose lay in creating broad and richly detailed photographic records of specific places and communities. For the rest of his career he pursued such projects in New England, France, Italy, the Hebrides, Morocco, Romania, Ghana, and other locales, producing numerous celebrated books. Together, these later series form one of the great photographic statements about modern experience.

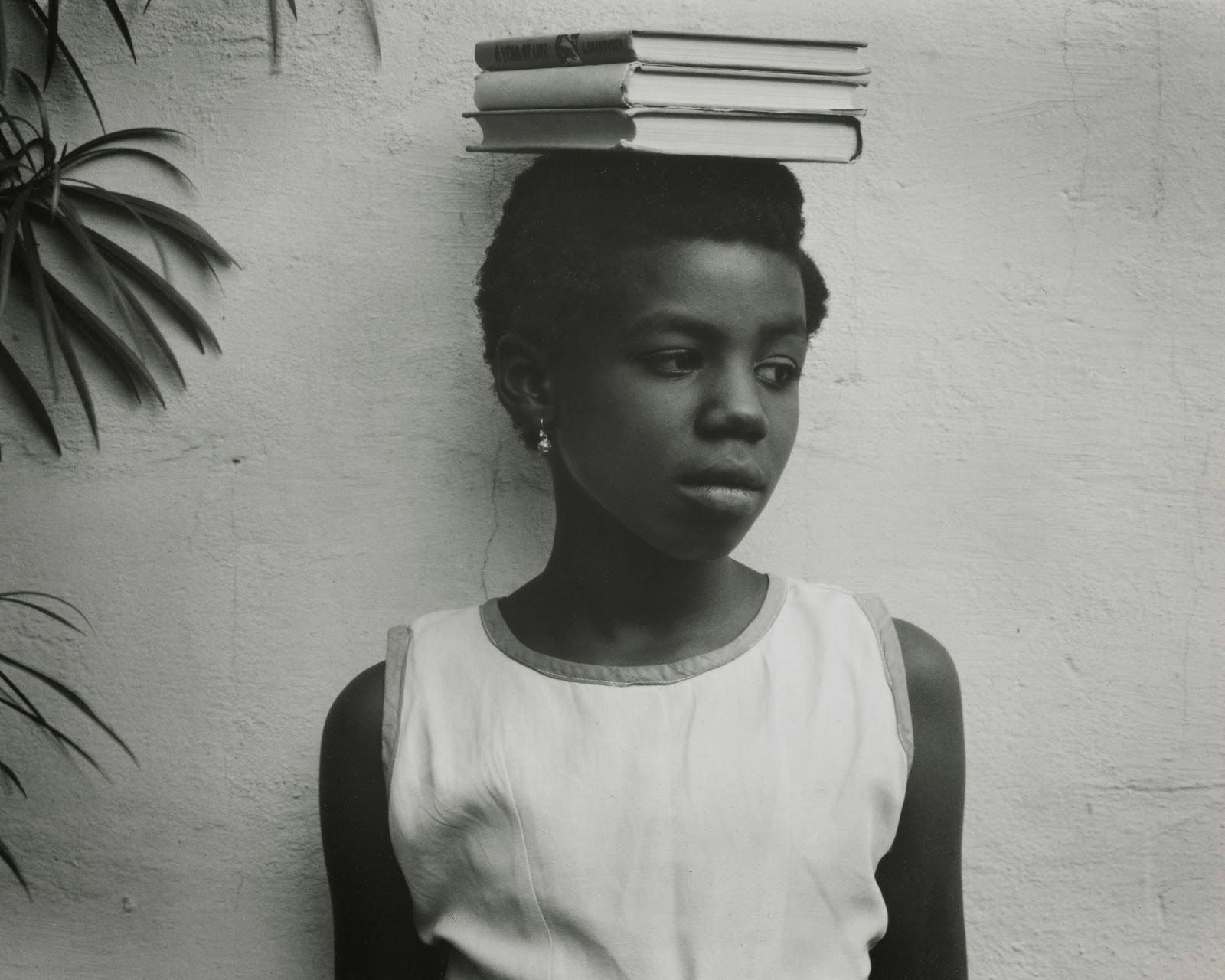

From his early experiments with street photography in New York to his sensitive portrayal of daily life in New England, Italy, and Ghana, Strand came to believe that the most enduring function of photography and his work as an artist was to reveal the essential nature of the human experience in a changing world. He was also a master craftsman, a rare and exacting maker of pictures

The River Neckar, Germany (1911).

On view also will be his innovative photographs of 1915–17 in which he explored new subject matter in the urban landscape of New York and new aesthetic ideas in works such as

These new directions in Strand’s photography demonstrated his growing interest both in contemporary painting—especially Cubism and the work of the American artists championed by Alfred Stieglitz—and in discovering for photography a unique means of expressing modernity. Strand’s work of this period includes candid, disarming portraits of people observed on the street—the first of their type—such as Blind Woman, New York (1916),

and Wall Street, New York (1915),

a seemingly random arrangement of tiny figures passing before the enormous darkened windows of the Morgan Trust Company Building, which illustrates Strand’s fascination with the pace of life and changing scale of the modern city.

His ideas about portraiture also extended to his growing preoccupation with photographic series devoted to places beyond New York, such as the southwest and Maine, where he would make seemingly ordinary subjects appear strikingly new. The exhibition will look at Strand’s widening engagement with his fellow artists of the Stieglitz circle, placing his works alongside a group of paintings by Georgia O’Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove, and John Marin, as well as photographs by Stieglitz, who played an important role in launching Strand’s career. These juxtapositions will reveal the rich interaction between Strand and his friends and peers during this time.

Elizabethtown, New Mexico (1930),

one of many photographs he made of abandoned buildings.

It will show Strand returning to a core motif—the portraiture of anonymous subjects—during the time when he lived in Mexico, from 1932 to 1934. This period abroad had a profound influence on him, deepening his engagement with leftist politics. Many of the works he created at this time, whether depicting individuals, groups of people, or even religious icons, convey in their exceptional compositions a deep empathy with his subjects. This can also be seen in his series devoted to Canada’s Gaspé Peninsula from the same decade.

Town Hall, New Hampshire (1946),

and portraits of people he met, including

Mr. Bennett, East Jamaica, Vermont (1943),

were reproduced inTime in New England. This book was published in 1950, the year Strand moved to France in response to a growing anti-Communist sentiment at home, and reflected his political consciousness. Strand described New England as “a battleground where intolerance and tolerance faced each other over religious minorities, over trials for witchcraft, over the abolitionists . . . It was this concept of New England that led me to try to find . . . images of nature and architecture and faces of people that were either part of or related in feeling to its great tradition.”

and fulfills his long-held ambition to create a major work of art about a single community. Strand’s photographs of Luzzara were published in Un Paese: Portrait of an Italian Village (1955).

The project led to the publication of Ghana: An African Portrait(1976),

In Strand’s later years, he would increasingly turn his attention close to his home in Orgeval, outside Paris, often addressing the countless discoveries he could make within his own garden. There he produced a remarkable series of still lifes. These were at times reflective of earlier work, but also forward-looking in their exceptional compositions that depict the beauty of myriad textures, free-flowing movement, and convey a quiet lyricism.

Strand’s second film, Redes(1936), conveys the artist’s growing social awareness during his time in Mexico. Released as The Wave in the U.S., the film is a fictional account of a fishing village struggling to overcome the exploitation of a corrupt boss. Native Land (1942) is Strand’s most ambitious film. Co-directed with Leo Hurwitz and narrated by Paul Robeson, it was created after his return to New York when Strand became a founder of Frontier Films and oversaw the production of leftist documentaries. Ahead of its time in its blending of fictional scenes and documentary footage, Native Land focuses on union-busting in the 1930s from Pennsylvania to the Deep South. When its release coincided with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, it was criticized as out-of-step with the nation, leading Strand to return exclusively to still photography.

On display will be early masterpieces such as

Title: Wall Street, New York

Artist: Paul Strand

Date: 1915

Credit line: © Paul Strand Archive, Aperture Foundation

Wall Street which depicts the anonymity of individuals on their way to work set against the towering architectural geometry and implied economic forces of the modern city. Strand’s early experiments in abstraction,

Title: White Fence, Port Kent, New York

Artist: Paul Strand

Date: 1916 (negative); 1945 (print)

Credit line: © Paul Strand Archive, Aperture Foundation

Abstraction, Porch Shadows and White Fence will also be shown, alongside candid and anonymous street portraits made secretly using a camera with a decoy lens, such as

Title: Blind Woman, New York

Artist: Paul Strand

Date: 1916

Credit line: © Paul Strand Archive, Aperture Foundation

Blind Woman.

The exhibition explores Strand’s experiments with the moving image with the film Manhatta(1920-21), the first time it has been screened in its entirety in the UK. A collaboration with the painter and photographer Charles Sheeler, Manhatta was hailed as the first avant-garde film, and traces a day in the life of New York from sunrise to sunset punctuated by lines of Walt Whitman poetry.

Strand’s embrace of the machine and human form is a key focus of the exhibition. In 1922, he bought an Akeley movie camera. The close-up studies he made of both his first wife Rebecca Salsbury and the Akeley during this time will be shown alongside the camera itself. Extracts of Strand’s later, more politicised films, such as Redes (The Wave), made in cooperation with the Mexican government are featured, as well as the scarcely-shown documentary Native Land, a controversial film exposing the violations of America’s workforce.

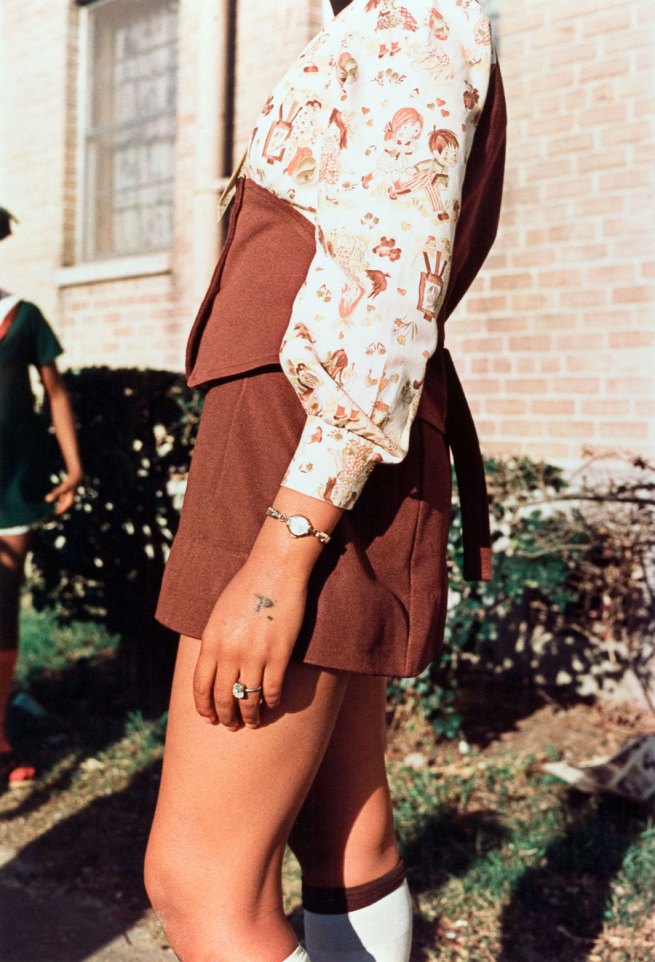

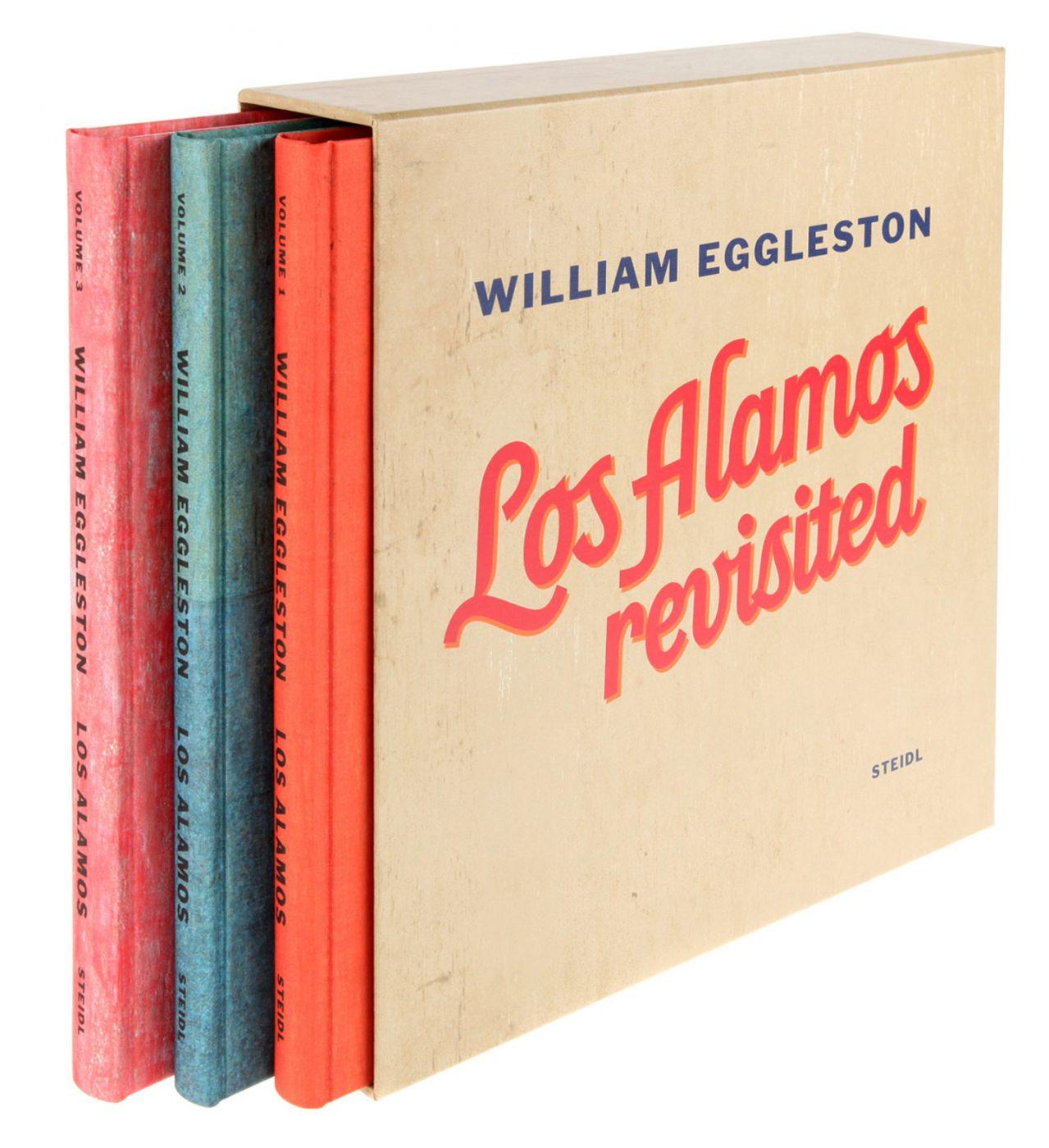

Strand travelled extensively and the exhibition will emphasise his international output from the 1930s to the late 1960s, during which he collaborated with leading writers to publish a series of photo books. As Strand’s career progressed, his work became increasingly politicised and focused on social documentary.

The exhibition will feature Strand’s first photobook

Time in New England (1950),

alongside others including a homage to his adopted home France and his photographic hero Eugène Atget,

La France de profil, made in collaboration with the French poet, Claude Roy.

Title: The Family, Luzzara (The Lusettis)

Artist: Paul Strand

Date: 1953 (negative); mid- to late 1960s (print)

Credit line: © Paul Strand Archive, Aperture Foundation

One of Strand’smost celebrated images, The Family, Luzzara, (The Lusetti’s) was taken in a modest agricultural village in Italy’s Po River valley for the photobook

Un Paese, for which he collaborated with the Neo-Realist writer, Cesare Zavattini. On display, this hauntingly direct photograph depicts a strong matriarch flanked by her brood of five sons, all living with the aftermath of the Second World War.

The images Strand took during his 1954 trip to the Scottish Hebrides reveal his methodical and meticulous approach to photography, much like a studio photographer in the open air. Strand conjured the sights, sounds and textures of the place steeped in the threatened traditions of Gaelic language, fishing and agricultural life of pre-industrial times.

The intimate set of black and white photographs include the V&A’s newly acquired image of a brooding youth,

Angus Peter MacIntyre, South Uist, Hebrides;

the patinated geology of

Rock, Lock Eynort, South Uist, Hebrides

and the all-encompassing expanse of the Atlantic Ocean depicted in

From the late 1950s to the mid-1960s, Strand photographed Egypt, Morocco and Ghana,all of which had gone through transformative political change.The exhibition will show Strand’s most compelling pictures from this period, including his tender portraits, complemented by remarkable street pictures showing meetings, political rallies and outdoor markets.

The exhibition will conclude with Strand’s final photographic series exploring his home and garden in Orgeval, France, where he lived with his third wife Hazel until his death in 1976.

(See the book and website here for more images from the garden)

The images are an intimate counterpoint to Strand’s previous projects and offer a rare glimpse into his own domestic happiness.

Paul Strand: Photography and Film for the 20th Century is part of an international tour organized by the Philadelphia Museum of Art in collaboration with Fundación MAPFRE and made possible by theTerra Foundation for American Art. It is curated by Peter Barberie, the Brodsky Curator of Photographs, Alfred Stieglitz Center at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, with the assistance of Amanda N. Bock,former Project Assistant Curator of Photographs·The exhibition is adapted for the V&Aby Martin Barnes, Senior Curator of Photography, V&A ·The nine newly acquired photographs from Paul Strand’s1954 Tir A’Mhurain series were purchased for the V&A with assistance from the Photographs Acquisitions Group.

The exhibition is accompanied by a substantial scholarly catalogue, Paul Strand: Master of Modern Photography, published by the Philadelphia Museum of Art in collaboration with Fundación MAPFRE; it is distributed in the trade by Yale University Press.

MORE IMAGES

Title: Couple, Rucăr, Romania

Artist: Paul Strand

Date: 1967

Credit line: © Paul Strand Archive, Aperture Foundation

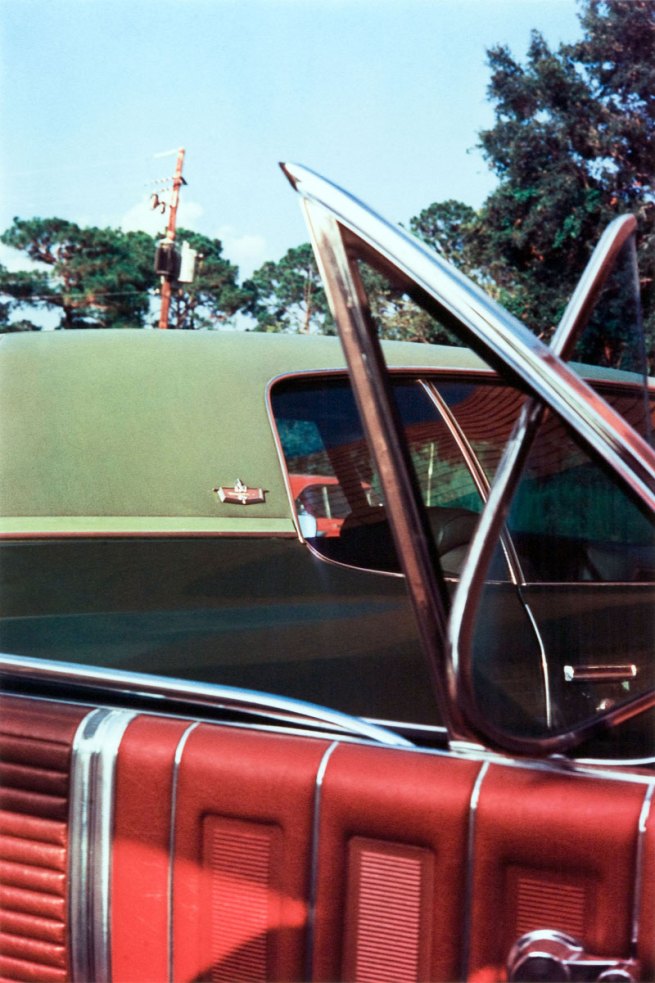

Title: Driveway, Orgeval

Artist: Paul Strand

Date: 1957

Credit line: © Paul Strand Archive, Aperture Foundation

Title: Milly, John and Jean MacLellan, South Uist, Hebrides

Artist: Paul Strand

Date: 1954

Credit line: © Paul Strand Archive, Aperture Foundation

Title: New Mexico

Artist: Paul Strand

Date: 1930

Credit line: © Paul Strand Archive, Aperture Foundation

Title: Rebecca, New York

Artist: Paul Strand

Date: 1921

Credit line: © Paul Strand Archive, Aperture Foundation

Title: Young Boy, Gondeville, Charente, France

Artist: Paul Strand

Date: 1951 (negative); mid- to late 1960s (print)

Credit line: © Paul Strand Archive, Aperture Foundation