Ansel Adams and the American West

SWANN Lot 70: Ansel Adams, Portfolio Four: What Majestic Word, In Memory of Russell Varian, 1963. Estimate $50,000 to $75,000. Sotheby's to present largest private collection of Ansel Adams photographs this December | ||

Ansel Adams, Yosemite Valley from Inspiration Point, Winter, Yosemite National Park. Mural-sized, sepia toned, mounted to Homasote board, framed, circa 1940, printed 1950s, 84 ¾ by 119 ¾ in. (215.3 by 304.2 cm.) Estimate $70/100,000. Courtesy Sotheby's.  Ansel Adams, Gravel Bars, American River, California. Mural-sized gelatin silver print, mounted to Homasote board, framed, 1950, probably printed in the 1950s, image: 106¾ by 82¾ in. (271.1 by 210.2 cm.) frame: 109 by 85 in. (276.9 by 215.9 cm.). Estimate $50/70,000. Courtesy Sotheby's. |

I knew little of these basic problems [of environmental conservation] when I first made snapshots in and around Yosemite. I was casually making a visual diary – recording where I had been and what I had seen – and becoming intimate with the spirit of wild places. Gradually my photographs began to mean something in themselves; they became records of experiences as well as of places. People responded to them, and my interest in the creative potential of photography grew apace. My piano suffered a serious rival. Family and friends would take me aside and say, ‘Do not give up your music; the camera cannot express the human soul' …I found that while the camera does not express the soul, perhaps a photograph can! …Stieglitz's doctrine of the equivalent as an explanation of creative photography opened the world for me. In showing a photograph he implied, ‘Here is the equivalent of what I saw and felt.' That is all I can ever say in words about my photographs; they must stand or fall, as objects of beauty and communication, on the silent evidence of their equivalence.” -- Ansel Adams |

For much of his early adulthood, Adams was torn between a career as a concert pianist versus one in photography; later, he famously likened the photographic negative to a musical score, and the print to the performance. Yet most museumgoers are only familiar with the heroic, high- gloss, high-contrast prints that Adams manufactured to order in the 1970s-80s, coinciding with the emergence of the first retail galleries devoted to photography; as performances, these later prints were akin to “brass bands.”

Much less familiar are the intimate prints, rich in the middle tones – the “chamber music” – that Adams crafted earlier in his career. The present show focuses on the masterful small-scale prints made by Adams from the 1920s into the 1950s. Already in this time period there is quite an evolution of printing style, from the soft-focus, warm-toned, painterly “Parmelian prints” of the 1920s; through the f/64 school of sharp-focused photography that he co-founded with Edward Weston and Imogen Cunningham in the 1930s; and, after the War, towards a cooler, higher-contrast printmaking approach.

Several singular examples are included in this exhibition. The extraordinarily rare print of Moonrise, Hernandez is one of the earliest extant – with its light gray (rather than deep black) sky with wispy clouds, it is literally “day and night” when compared to his much more common, much darker, printings from the 1970s and 1980s.

Ansel Adams

Aspens, Northern New Mexico, 1958

Vintage silver gelatin print

16 x 20 inches (frame size)

Image courtesy of art2art Circulating Exhibitions

© Trustees of The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

The print of Frozen Lake and Cliffs is considered the finest vintage print extant; it was the announcement for the blockbuster show “Ansel Adams at 100,” curated by the late John Szarkowski.

Monolith, the Face of Half Dome is represented by two contrasting examples: the vintage 6x8 inch Parmelian print from 1927, and a rare transitional 16x20 inch matte-surface mounted print from the early 1940s which shows Adams first experimenting with scale but not yet consistently committed to glossy paper stock.

Clearing Winter Storm, Yosemite National Park, California, 1938

Photograph by Ansel Adams

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Photograph by Ansel Adams

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Clearing Winter Storm, taken from Inspiration Point, is Adams' most celebrated Yosemite view. The exhibit features the earliest known vintage print of this seminal image (a 1938 date appears on his original typewritten label), which just surfaced in 2005. Hitherto this photograph had generally been dated “circa 1944”; it is noteworthy that such an iconic image can be re-dated in this manner by a full six years.

Ansel Adams, American (1902-1984), Roaring River Falls, ca. 1925, vintage silver gelatin print, framed: 18 x 14 inches, Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg, ©2013 The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

|

Ansel Adams, American (1902-1984), Trees and Snow, 1933, vintage silver gelatin print, framed: 20 x 16 inches, Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg, ©2013 The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

|

![[cliff with narrow triangular face in shadow at left, valley view]](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2016/08/The-Sentinel-Yosemite-Valley-ca.-1923-1024x768.jpg)

Ansel Adams, The Sentinel, Yosemite Valley, ca (1923). Courtesy of National Park Service.

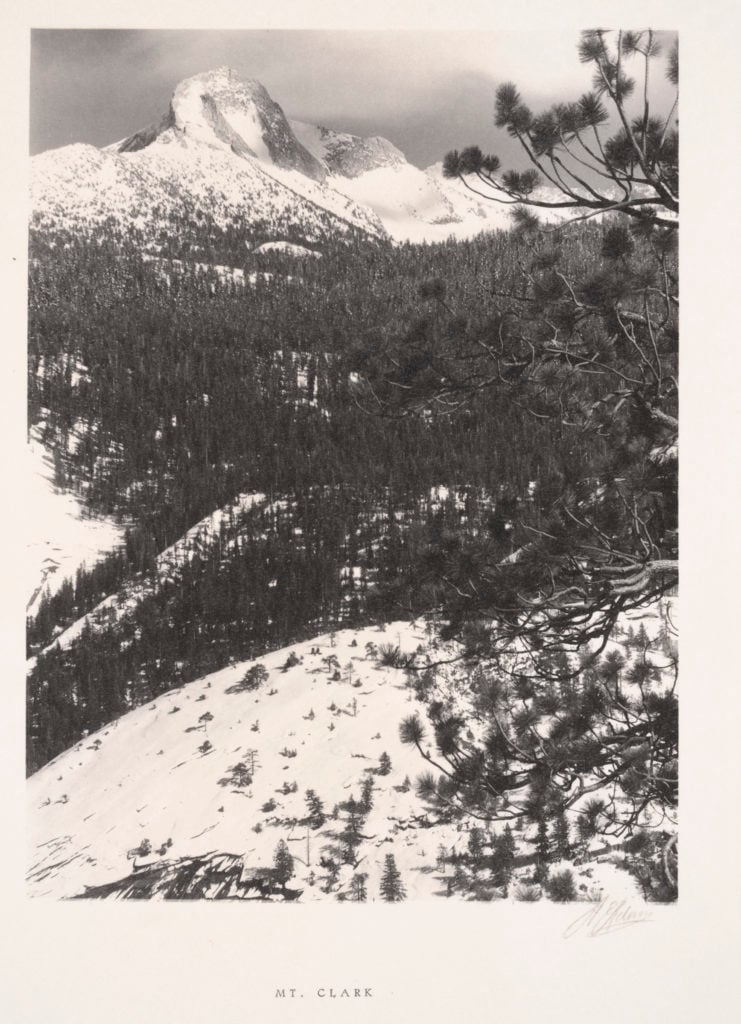

Ansel Adams, Mount Galen Clark, Yosemite National Park (1927). Courtesy of Fenimore Art Museum © 2015 The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust.

![[dark valley view without waterfall, Half Dome in center distance with pale lcloud above it, layer of pale mackerel clouds above] Do not crop, alter photograph. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. All scans provided by the Center are solely and specifically for one-time, single use reproduction as noted on CCP Invoice and related documents. NOTE: The Center RETAINS COPYRIGHT on ALL digital reproduction FILES with embedded metadata provided from the Center's Collections (and ANY related derivatives which may be generated by client.) Scans of photographs provided by the Center for the above-detailed one-time reproduction purpose may not be digitally archived by the client, publisher, any subcontractor and/or agent who may be working on this project. All original and derivative digital copies of image files provided must be deleted from all digital storage media once the publication layout itself has been designed and archived.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2016/08/CCP_84091086_m-1024x806.jpg)

Ansel Adams, Yosemite Valley, High Clouds, from Tunnel Esplanade, Yosemite National Park, California (1940). Courtesy of Fenimore Art Museum © 2015 The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust.

© Ansel Adams

Mount Williamson, from Manzanar (c. 1944)

and Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico (1941), within the context of an unexpected and unfamiliar body of photographs, including

North Palisades, from Windy Point (1936)

and Two Dead Trees Against Black Sky, Sierra Nevada (1925). The photographer identified deeply with the culture and geography of the American West. Adams made hundreds of photographs of the American landscape and his pictures, according to Mr. Szarkowski, “have revised our sense of what we mean when we say landscape.” As Mr. Szarkowski states in his catalogue essay, “Adams’s pictures . . . demonstrate that even in the great theatrical diorama of Yosemite, the mountains are no more miraculous than a few blades of grass floating on good water. His pictures have enlarged our visceral knowledge of things that we do not understand.”

Ansel Adams was born in San Francisco in 1902, lived there for 60 years, and spent the last two decades of his life in Carmel Highlands, on the Big Sur Coast. As a youth he first photographed Yosemite Valley with a Kodak Brownie box camera, and Yosemite became the lifelong subject for which he is best known. Starting in 1919, Adams spent much time in Yosemite and the Sierra and served as photographer on the Sierra Club Outings until 1936. The process of Adams’s development as an artist is documented in the proof albums that he made on these outings, three of which are included in this exhibition. In his later life, Adams became an important educator and proponent for the medium of photography, an advocate for the Sierra Club, and America’s best-known environmentalist.

Storm, Yosemite Valley, California, 1938

Photograph by Ansel Adams

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

“I knew little of these basic problems [of environmental conservation] when I first made snapshots in and around Yosemite. I was casually making a visual diary – recording where I had been and what I had seen – and becoming intimate with the spirit of wild places. Gradually my photographs began to mean something in themselves; they became records of experiences as well as of places. People responded to them, and my interest in the creative potential of photography grew apace. My piano suffered a serious rival. Family and friends would take me aside and say, ‘Do not give up your music; the camera cannot express the human soul' _…I found that while the camera does not express the soul, perhaps a photograph can! …Stieglitz's doctrine of the equivalent as an explanation of creative photography opened the world for me. In showing a photograph he implied, ‘Here is the equivalent of what I saw and felt.' That is all I can ever say in words about my photographs; they must stand or fall, as objects of beauty and communication, on the silent evidence of their equivalence.”

-- Ansel Adams

Ansel Adams – photographer, musician, naturalist, explorer, critic and teacher – was a giant in the field of landscape photography. His work can be viewed as the end of an arc of American art concerned with capturing the “sublime” in the unspoilt Western landscape. This tradition includes the painters Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Cole and Thomas Moran, and the photographers Carleton Watkins, Timothy O'Sullivan and William Henry Jackson.

For much of his early adulthood, Adams was torn between a career as a concert pianist versus one in photography; later, he famously likened the photographic negative to a musical score, and the print to the performance. Yet most museumgoers are only familiar with the heroic, high- gloss, high-contrast prints that Adams manufactured to order in the 1970s-80s, coinciding with the emergence of the first retail galleries devoted to photography; as performances, these later prints were akin to “brass bands.” Much less familiar are the intimate prints, rich in the middle tones – the “chamber music” – that Adams crafted earlier in his career.

This show focused on the masterful small-scale prints made by Adams from the 1920s into the 1950s. Already in this time period there is quite an evolution of printing style, from the soft-focus, warm-toned, painterly

“Parmelian prints” of the 1920s; through the f/64 school of sharp-focused photography that he co-founded with Edward Weston and Imogen Cunningham in the 1930s; and, after the War, towards a cooler, higher-contrast printmaking approach.

Several singular examples were included in this exhibition. The extraordinarily rare print of Moonrise, Hernandez is one of the earliest extant – with its light gray (rather than deep black) sky with wispy clouds, it is literally “day and night” when compared to his much more common, much darker, printings from the 1970s and 1980s.

The print of Frozen Lake and Cliffs is considered the finest vintage print extant; it was the announcement for the recent blockbuster show “Ansel Adams at 100,” curated by the late John Szarkowski. Monolith, the Face of Half Dome is represented by two contrasting examples: the vintage 6x8 inch Parmelian print from 1927, and a rare transitional 16x20 inch matte-surface mounted print from the early 1940s which shows Adams first experimenting with scale but not yet consistently committed to glossy paper stock.

Clearing Winter Storm, taken from Inspiration Point, is Adams' most celebrated Yosemite view. The exhibition featured the earliest known vintage print of this seminal image (a 1938 date appears on his original typewritten label), which just surfaced in 2005. Hitherto this photograph had generally been dated “circa 1944”; it is noteworthy that such an iconic image can be re-dated in this manner by a full six years.

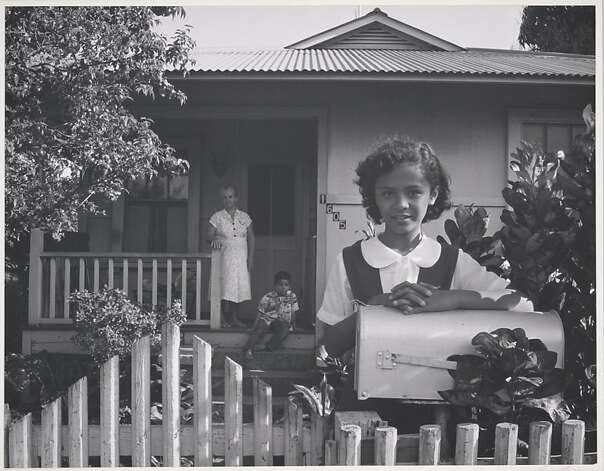

Ansel Adams’ photographs of Hawaii were also commissioned, first in 1948 for the Department of the Interior, and in 1957 for a commemorative publication for Bishop National Bank of Hawaii (currently First Hawaiian Bank). Like O’Keeffe, Adams sought to reveal a nontraditional view of the islands, aiming to capture a sense of place with his unique style and showing the viewer the connection between the land and its inhabitants.

In a letter written by Adams in 1938 he explains, “If I have any niche at all in the photographic presentation of America, I think it would be chiefly to show the land and the sky as the settings for human activity.”

Ansel Adams' "Buddhist Grave markers and Rainbow, Paia, Maui, Hawaii," 1956, ;Collection Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona. Photo: ©First Hawaiian Bank

Ansel Adams' "Sanchez Family, Wailuku Plantation, Maui," 1957, Collection Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona Photo: ©First Hawaiian Bank

Ansel Adams' "On the Island of Molokai, Hawaii," c. 1957, ;Collection Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Photo: ©First Hawaiian Bank

Ansel Adams' "Fish pond at dawn near Kaunakakai, Molokai," 1958, Plate 17 from "The Islands of Hawaii," ;Collection First Hawaiian Bank, Photo: ©First Hawaiian Bank

Ansel Adams' "Roots, Foster Garden, Hawaii," 1948, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Henry B. Clark, Jr.,

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984), “Orchard”, Portola Valley, California, c. 1940. Gelatin silver print. Photo; Courtesy: Turtle Bay Exploration Park, Redding, CA. ©Ansel Adams Publishing Right

Oak Tree, Snowstorm

Trailer Camp Children

Sand Dunes

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1&width=600)

No comments:

Post a Comment