Robert Frank, one of the most influential photographers of the 20th century’s postwar years, revolutionized classic reportage and street photography. Over a period spanning six decades, this Swiss - American artist created photographs, experimental montages, books, and films.

The Albertina is showing selected works and series that trace Robert Frank’s development: from his early photojournalistic images created on trips through Europe to the pioneering work group The Americans and on to his later, more introspective projects, over 100 works will serve to illuminate central aspects of his oeuvre, which has never before seen presentation in Austria. Dynamism and Contrasts Born in Zurich in 1924 to a German - Jewish family, Robert Frank was granted Swiss citizenship only just before the end of the Second World War. He began his training as a photographer in 1941 and received thorough schooling in the profession’s tools and techniques.

The motifs of his initial documentary pictures, which were devoted to national identity as symbolized by parades and flags, proved to be ones that he would return to later in his career. Upon his emigration from Switzerland to the USA in 1947, the artist established an expressive pictorial language that broke with that era’s photographic conventions, which were defined in terms of refined composition and perfect tonal values. At the suggestion of Alexey Brodovitch, art director of Harper’s Bazaar, Frank began using a 35 mm Leica that enabled him to adopt an intuitive and spontaneous way of working. The result was a new pictorial language char acterized by strong contrasts, dynamism, and blurry images.

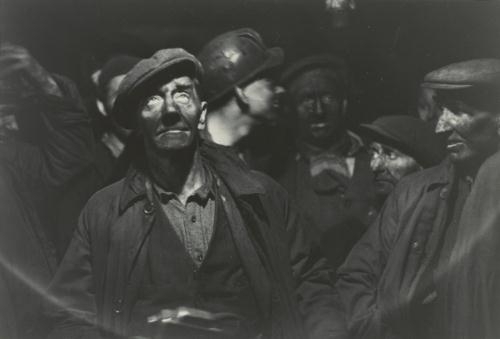

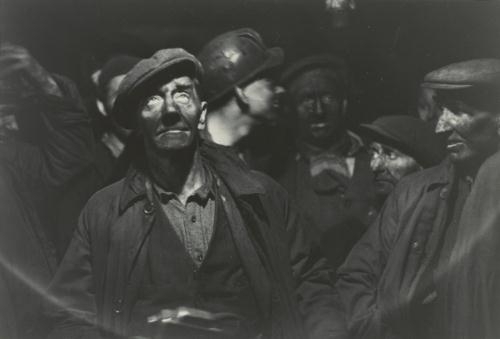

He went on to produce work groups such as People You Don’t See (1951), in which he devoted himself to the everyday lives of six individuals from his Manhattan apartment complex. A reportage on London (1951 – 1953) characterizes this metropolis by way of the contrast between wealthy bankers and people from the lower classes, and Great Britain was also the setting of his series on the hard daily life of Welsh miner Ben James (1953).

By way of contrast, Frank’s photographs from Paris (1949 – 1952) feature a more lyrical tone. Thanks to his intuitive approach to photography, Frank’s works lend expression to a decidedly subjective gaze featuring a personal take on what he experienced and saw.

The Americans

Robert Frank’s artist book The Americans , comprised of photos shot between 1955 and 1957, made photographic history: captured on a series of road trips through the United States, these images expose the postwar “American way of life” in grim black and white, revealing a reality of pervasive racism, violence, and consumerism. Due to these photos’ failure to uphold America’s self - image at the time, he at first only managed to have this book published in Europe. Frank’s coming of age as an artist went hand - in - hand with that of jazz, beat literature, and the improvisatory style of abstract expressionism — and his own expressivity is of a raw, improvised, and spontaneous character. Jack Kerouac extolls Frank’s gaze in the foreword to the book’s US edition with the following words: “The humor, the sadness, the EVERYTHING-ness and American-ness of these pictures!”

It was these qualities that underpinned Robert Frank’s success in creating one of the most influential photographic works of the postwar period, one that effected a sustained renewal of street photography. Announced by Frank as the “visual study of a civilization,” The Americans contained motifs that, in the midst of the Cold War, had not yet been deemed worthy of depiction. He was interested in everyday phenomena of leisure and pop culture, but also documented isolation, the plights of minorities, and racism:

Robert FrankTrolley – New Orleans, 1956Gelatin silver print

© Robert Frank, Sammlung Fotostiftung Schweiz, Eigentum der Schweizerischen Eidgenossenschaft, Bundesamt für Kultur, Bern

Touching Montages

With his 1958 photo series From the Bus, which contains photos of passers - by casually taken from a moving bus, Frank set off in a new, more experimental direction. And eventually, in no small part due to his dissatisfaction with the limited possibilities of individual pictures, he abandoned photography and turned to film. There, Frank often used his own photographs in order to examine his memories and past, producing several autobiographical filmic essays. Upon his return to photography at the beginning of the 1970s, the form and content of his works changed yet again: autobiographical themes such as the tragic loss of his children are visualized via multi - image montages and sequences that frequently also contain texts. In these, Frank succeeded in poetically amalgamating different media and their influences upon one another.

The Austrian Film Museum will be presenting a comprehensive retrospective of Robert Frank’s filmic oeuvre in cooperation with the Albertina from 10 to 27 November.

Wall Texts

Robert Frank

Robert Frank (b. November 9, 1924, Zurich, Switzerland) ranks among the most influential photographers of the postwar years. The photographs, artist books, and films he created over a period of six decades were conceived in reference to one another. This exhibition presents an overview of the artist’s most important phases as a photographer, which in addition to photojournalistic works and reportages also comprise conceptual series and experimental photomontages. The focus is on the period between the1940s and the 1980s, during which time Frank revolutionized conventional reportage and street photography.

After a profound training as a photographer, the artist emigrated from Switzerland to the United States in 1947 There he established an expressive pictorial language that broke away from conventional photography, which defined its elf by elaborate compositions and perfect tonal values. In what was an intuitive photographic practice, he lent expression to a decidedly subjective vision emphasizing his personal experiences of what he had seen. Frank’s pioneering group of works entitled The Americans, published as an artist book in 1958/59, marks a climax of this development.

Shortly afterwards Frank abandoned photography in favor of film and only came to revisit the photographic medium from 1972 on. In Frank’s films and books, his photo graphs have undergone recontextualization. In their combination of photography, text, and graphic design, his photo books exhibit progressive pictorial solutions placed on an equal footing with his photographic prints. In his films, Frank frequently used h is own photographs to explore his memories and past. Juxtapositions of the various media reveal their mutual interdependence. If not indicated otherwise, all photographs are gelatin silver prints.

Contact Prints from Switzerland

Starting in 1941, Robert Frank learned the technique of photography in the studios of several Swiss photographers. Under the influence of Michael Wolgensinger, a commercial and reportage photographer, he made his first documentary studies on Switzerland. F rank photographed then - popular themes, such as landscapes, sporting events, festivities taking place on national holidays, and the local population in traditional costumes. These pictures are to be seen in the context of the country’s so - called “spiritual national defense,” an ideology that had been promoted by the Swiss government since the mid - 1930s and was meant to strengthen patriotism and the people’s opposition against National Socialism through a revival of national values. Pictures of parades and fl ags addressing issues of national identity and such stylistic devices as a low camera angle already anticipated later works. Coming from a Jewish family, Frank only became a naturalized Swiss citizen a few days before the end of the war (his father, who was from Germany, was stateless due to the “Reich Citizenship Law” of 1935). Both his family’s experience and fears related to the threatening closeness of Nazi Germany and Switzerland’s intellectual and cultural narrow - mindedness led to his emigration to the United States in 1947.

Black White and Things

After moving to New York, Robert Frank worked as an assistant photographer to Alexey Brodovitch, the art director of Harper’s Bazaar, for several months. Upon the latter’s recommendation, Frank began using a 35mm - Leica, which facilitated an intuitive and spontaneous approach to photography. This resulted in a new pictorial language marked by stark contrasts, dynamism, and blurry images. In New York and during his travels through Europe, Frank shot pictures intended for publication in magazines. Influenced by the works of Henri Cartier - Bresson and André Kertész, he took lyrical photographs of flowers, park chairs, and pedestrians in Paris between 1949 and 1952. Whereas having still captured the French metropolis in the form of individual impressions, Frank conceived comprehensive narratives when in England. In London he focused on wealthy bankers (1951 – 53) staged in nuanced grays and elegant compositions.

By contrast, at around the same time he also produced a series of pictures showing the Welsh pitman Ben James (1953). Contrary to the ambition of conventional reportage photography to deliver special moments and social messages, his photographs, thanks to their expressivity, convey the immediate experienc e of the miner’s harsh working life. Due to the formal radicalness of his pictures, most magazines refused to publish them. Frank selected some of them for his artist book Black White and Things which was designed by the Swiss commercial artist Werner Zryd. The linear and narrative structure of photo books common at the time was neglected in favor of associatively composed chapters and subjective sequences of images.

People You Don’t See

Robert Frank conceived the series People You Don’t See in 1951 for a competition organized by Life magazine. In these pictures, Frank described the daily routine of six individuals living and working in his Manhattan neighborhood. He modeled the pictures on popular photo - essays telling thematically clear - cut stories, wit h an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. That the photographs were complemented by explanatory captions was untypical of Frank. Due to its narrative layout, People You Don’t See is one of Frank’s classic series. However, what is unusual in the context of picture reportage is how he concentrated on the realities of everyday life, which can also be encountered in other works by Frank.

The Guggenheim - Trips

Disappointed that magazines had declined his reportages, Robert Frank applied for two Guggenheim scholarships upon the recommendation of the photographer Walker Evans. They allowed him to undertake three extensive journeys across the United States from which his hitherto most ambitious and radical project emerged. Announced by Frank as a “visual study of civilization,” it exposed characteristic aspects of US society during the Cold War in terms of patriotism, racism, religion, politics, consumerism, and leisure culture. If the artist had explored social patterns with a subjective gaze in earlier works, he now sharpened his approach: he took to spontaneously photographing ordinary motifs of high symbolic content, frequently without looking through the viewfinder of his 35 - mm camera , and reversed their meaning through his grim imagery.

Such patriotic motifs as flags are described as trivial; politicians are characterized as egomaniacal and narcissistic; the inhabitants appear lonely and isolated. Frank’s style developed in line with contemporary US - American art. Similarly, intuition and improvisation were central devices in Beat literature and Abstract Expressionism. Moreover, in the 1930s and 1940s the photographers of the Federal Security Administration (FSA) had already captured ma rginal groups of society in momentary pictures to formulate a visual critique of American society.

Les Américains/The Americans

In 1958, Robert Frank released eighty - three photographs from his Guggenheim trips as a book that first appeared with the French publisher Robert Delpire. In allusion to Henri Cartier - Bresson’s publication Les Européens, Delpire chose the title Les Américains. The following year the English edition The Americans was published by Grove Press. Both titles are considered incunabula of the artistic photo book genre. Robert Frank defined the format and layout, with a single photograph appearing on every right - hand page. He divided the book into four parts, each of which addressed themes of his personal view of America. As had already been the case with his book Black White and Things, the layout broke with the conventional, narrative form of a book, as the artist grouped the pictures according to thematic, formal, conceptual, and language - based criteria. In the French version, the photos were combined with texts criticizing America by such authors as William Faulkner, Simone de Beauvoir, and Walt Whitman against Frank’s will, which placed the pictures in a socio - documentary context. The American edition, on the other hand, was solely accompanied by an introductory text by Beat poet Jack Kerouac. Upon its appearance, The Americans met with fervent criticism. Frank’s perspective of the United States as a Swiss and thus as an outsider conflicted with the country’s self - portrayal and self - perception. In contemporary reviews, the photographs were described as documents of maliciousness and hopelessness, and Frank was identified as a morose man hating America. At the same time, the publication was greatly praised amongst professional circles and has received wide and lasting response since the 1960s.

Contact Sheets and Work Prints

The harvest of Robert Frank’s photographic travels through the United States took up 767 rolls of film. Relying on contact sheets, the artist examined the 27,000 negatives these rolls contained and picked one thousand pictures, which he developed as small - form at work prints. These were narrowed down further to a selection of just under one hundred final prints. The contact sheets and work prints allow us to reconstruct the genesis of The Americans and shed light on Frank’s working method. While the photographer sometimes achieved a satisfactory result with the first push on the camera button, he occasionally captured the same motif a number of times before he chose one of the pictures. The lack of definition and faulty exposure of many negatives leave no doubt bout Frank’s intuitive approach. The unceasing repetition of individual motifs evidences how methodically the artist proceeded in some cases. Before setting out, Frank had already defined such highly symbolic motifs as flags, cowboys, motorbikes, parades, and politicians, which he continued to photograph after the end of his travels to complete their range.

On Independence Day, the Fourth of July, he returned to Jay in the north of the state of New York, for example, to photograph a transparent flag.

Coney Island and From the Bus

Afraid of repeating himself and dissatisfied with the limited possibilities of the single image, Frank abandoned photography and turned his attention to film after the publication of The Americans.

Coney Island and From the Bus are two of his last groups of works before he began to pursue a career as a filmmaker. Coney Island captures the leisure and entertainment neighborhood in the eponymous borough of Brooklyn in New York City on Independence Day, the Fourth of July. Frank’s gloomy photographs emphasize the bleakness of the place and aspects of human solitude instead of rendering the joyful festivities and the patriotic attitude traditionally displayed on the national holiday. His focus on the predominantly Afro - American population reflects the artist’s disillusionment with racism, which he had been confronted with repeatedly when travelling the United States. Whereas Coney Island seamlessly follows in the vein of the pictorial language that characterizes The Americans, the serial conception of From the Bus clearlyanticipates Frank’s turn toward film. The series pictures passing people casually shot from a New York City bus. The representation of unspectacular moments, “unartistic” compositions, and photographing along a prede fined route already prefigure the conceptual photography of the 1960s.

Conversations in Vermont

After feature films like the beatnik piece Pull My Daisy (1959), Robert Frank shot a series of autobiographical essay films. In these films he often used his own photos to deal with his personal memories, family history, or attitude toward his work as an artist. In Conversations in Vermont (1969), we find Frank filming pictures from his cycles London, Paris, and The Americans as he seeks to fathom his role as a father and artist. Visiting his children, Andrea and Pablo, in the state of Vermont, he confronted them with his iconic photographs. Andrea and Pablo reacted evasively and were hardly interested in the pictures and their father’s past. This meeting led Frank to admit that he had pursued his career as an artist without showing consideration for his family.

Home Improvements

The video Home Improvements ( 1985) is one of Robert Frank’s autobiographical works in which he deals with his life in a diary - like manner. The melancholy piece revolves around Frank’s worries over his wife June Leaf and his son Pablo, who were in the hospital at the time. At some point, the film refers to photographs showing mainly Pablo and pictures from the series The Americans. He used these photographs to inquire into his past and the public perception of his work as an artist. For example, we see Frank filming a friend brutally drilling several holes through a batch of older prints. This act is to be read as a comment on a fierce litigation he conducted against a group of gallery owners in the early 1980s. He had sold the rights to his photographs to them in 1977 in order to fund h is films. When the gallery owners started turning the pictures to account against Frank’s intentions, he put up a struggle against the loss of control over his oeuvre and its commercialization going hand in hand with it. Though he finally succeeded, he found himself unable to trust in the art market from that time on.

The Return to Photography: Experimental Photo Montages/The Late Work

In the early 1970s, Robert Frank began to take photographs again. Single pictures gave way to experimental montages in which he combined pictures with words and sentence fragments. Now using a Polaroid instant camera, Frank exposed several negatives on the same paper or mounted photos next to one another. He also inscribed and scratched the negatives and prints. Both the photographer’s subjective comments and the montage technique were owed to the influence of his filmmaking. Pictures of his immediate surroundings lend expression to the artist’s world of inner emotions.

Through landscape impressions of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, where Frank has lived since the 1970s,

and For Andrea 1954 – 1974 visualize the artist’s emotions about the early death of his daughter, who died in a plane crash in 1974. His work also reflects the great strain under which the artist suffered due to his son Pablo’s progressing physical and mental illness and his death in 1994.

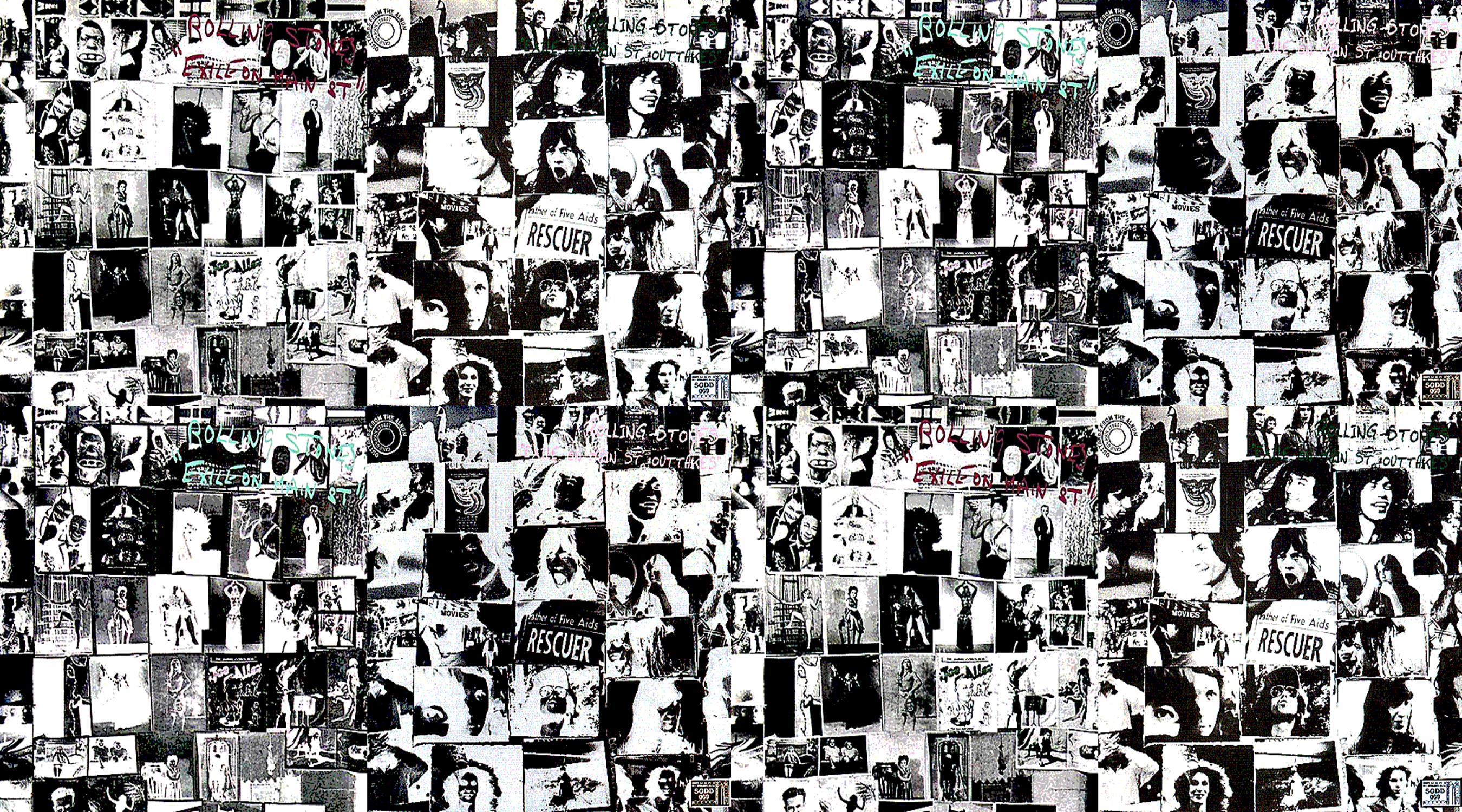

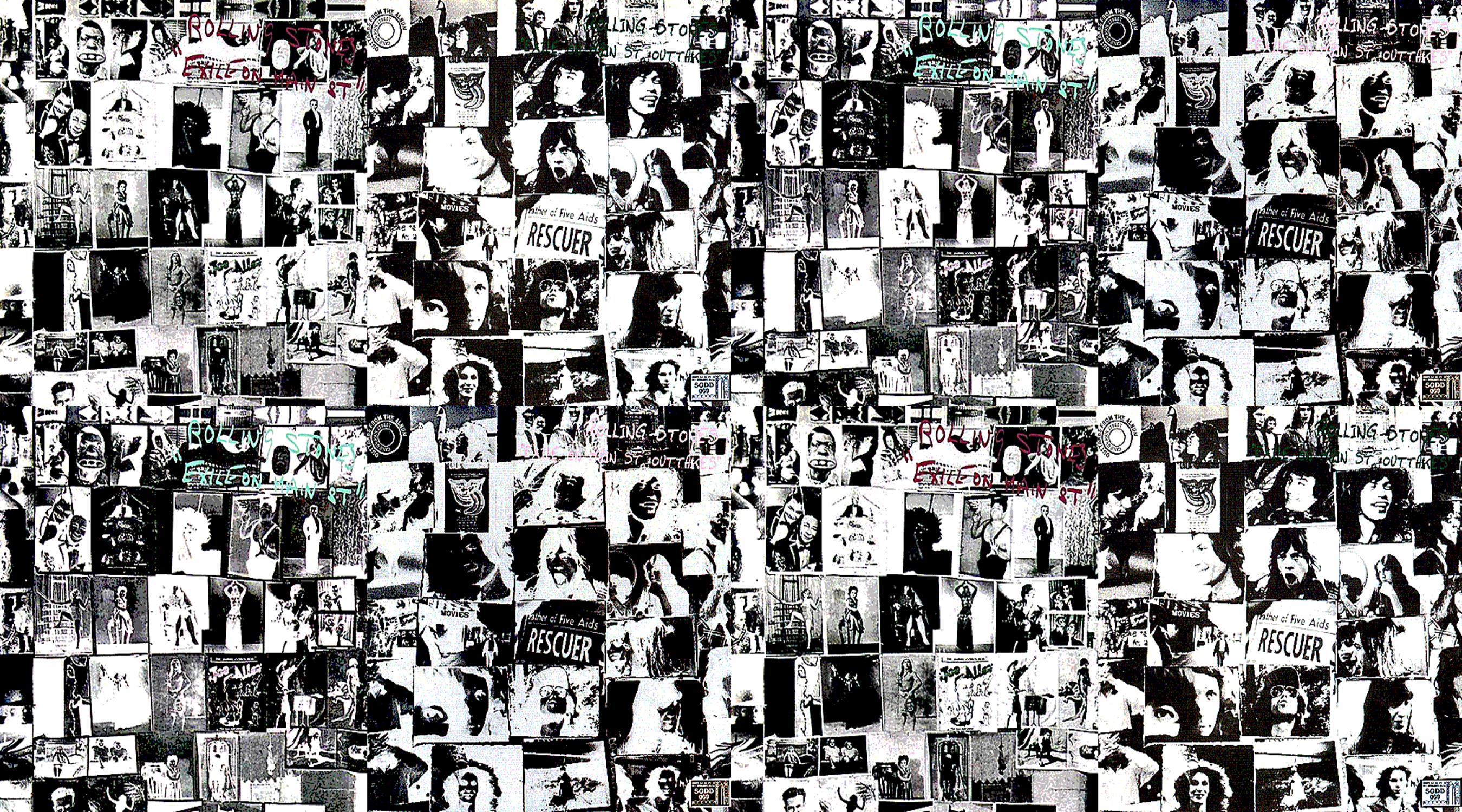

As he had done in his films, Frank, intent on venting his critical attitude toward his artistic past, incorporated pictures he had taken for The Americans in his new works. One example is the photograph of a priest on the banks of the Mississippi River, which had been published in The Americans. Collaborating with the Rolling Stones in the early 1970s, he used it for

the montage on the back cover for the group’s album Exile on Main Street. In the case of the photo work of the same name, for which Frank again fell back on the picture of the priest, he duplicated the photograph and combined it with a line from the song “Sweet Virginia,” to be found on the Rolling Stones’ album.

The work testifies to the use of older motifs in different contexts so typical of the artist’s late work.

The Lines of My Hand

Robert Frank’s book The Lines of My Hand came out in 1972. Originally published by Yugensha in Japan, its American edition was put out by Lustrum Press. The volume assembles pictures from all periods of the photographer’s production under subjective aspects. Like the photographs and films of that time, the personal arrangement of the pictures and their combination with diary - like texts serve as vehicles for the artist’s introspective self - reflection. The confrontation with his old pictures during his work on the book triggered a new return to photography.

Robert Frank

Robert Frank (b. November 9, 1924, Zurich, Switzerland) ranks among the most influential photographers of the postwar years. The photographs, artist books, and films he created over a period of six decades were conceived in reference to one another. This exhibition presents an overview of the artist’s most important phases as a photographer, which in addition to photojournalistic works and reportages also comprise conceptual series and experimental photomontages. The focus is on the period between the1940s and the 1980s, during which time Frank revolutionized conventional reportage and street photography.

After a profound training as a photographer, the artist emigrated from Switzerland to the United States in 1947 There he established an expressive pictorial language that broke away from conventional photography, which defined its elf by elaborate compositions and perfect tonal values. In what was an intuitive photographic practice, he lent expression to a decidedly subjective vision emphasizing his personal experiences of what he had seen. Frank’s pioneering group of works entitled The Americans, published as an artist book in 1958/59, marks a climax of this development.

Shortly afterwards Frank abandoned photography in favor of film and only came to revisit the photographic medium from 1972 on. In Frank’s films and books, his photo graphs have undergone recontextualization. In their combination of photography, text, and graphic design, his photo books exhibit progressive pictorial solutions placed on an equal footing with his photographic prints. In his films, Frank frequently used h is own photographs to explore his memories and past. Juxtapositions of the various media reveal their mutual interdependence. If not indicated otherwise, all photographs are gelatin silver prints.

Contact Prints from Switzerland

Starting in 1941, Robert Frank learned the technique of photography in the studios of several Swiss photographers. Under the influence of Michael Wolgensinger, a commercial and reportage photographer, he made his first documentary studies on Switzerland. F rank photographed then - popular themes, such as landscapes, sporting events, festivities taking place on national holidays, and the local population in traditional costumes. These pictures are to be seen in the context of the country’s so - called “spiritual national defense,” an ideology that had been promoted by the Swiss government since the mid - 1930s and was meant to strengthen patriotism and the people’s opposition against National Socialism through a revival of national values. Pictures of parades and fl ags addressing issues of national identity and such stylistic devices as a low camera angle already anticipated later works. Coming from a Jewish family, Frank only became a naturalized Swiss citizen a few days before the end of the war (his father, who was from Germany, was stateless due to the “Reich Citizenship Law” of 1935). Both his family’s experience and fears related to the threatening closeness of Nazi Germany and Switzerland’s intellectual and cultural narrow - mindedness led to his emigration to the United States in 1947.

Black White and Things

After moving to New York, Robert Frank worked as an assistant photographer to Alexey Brodovitch, the art director of Harper’s Bazaar, for several months. Upon the latter’s recommendation, Frank began using a 35mm - Leica, which facilitated an intuitive and spontaneous approach to photography. This resulted in a new pictorial language marked by stark contrasts, dynamism, and blurry images. In New York and during his travels through Europe, Frank shot pictures intended for publication in magazines. Influenced by the works of Henri Cartier - Bresson and André Kertész, he took lyrical photographs of flowers, park chairs, and pedestrians in Paris between 1949 and 1952. Whereas having still captured the French metropolis in the form of individual impressions, Frank conceived comprehensive narratives when in England. In London he focused on wealthy bankers (1951 – 53) staged in nuanced grays and elegant compositions.

By contrast, at around the same time he also produced a series of pictures showing the Welsh pitman Ben James (1953). Contrary to the ambition of conventional reportage photography to deliver special moments and social messages, his photographs, thanks to their expressivity, convey the immediate experienc e of the miner’s harsh working life. Due to the formal radicalness of his pictures, most magazines refused to publish them. Frank selected some of them for his artist book Black White and Things which was designed by the Swiss commercial artist Werner Zryd. The linear and narrative structure of photo books common at the time was neglected in favor of associatively composed chapters and subjective sequences of images.

People You Don’t See

Robert Frank conceived the series People You Don’t See in 1951 for a competition organized by Life magazine. In these pictures, Frank described the daily routine of six individuals living and working in his Manhattan neighborhood. He modeled the pictures on popular photo - essays telling thematically clear - cut stories, wit h an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. That the photographs were complemented by explanatory captions was untypical of Frank. Due to its narrative layout, People You Don’t See is one of Frank’s classic series. However, what is unusual in the context of picture reportage is how he concentrated on the realities of everyday life, which can also be encountered in other works by Frank.

The Guggenheim - Trips

Disappointed that magazines had declined his reportages, Robert Frank applied for two Guggenheim scholarships upon the recommendation of the photographer Walker Evans. They allowed him to undertake three extensive journeys across the United States from which his hitherto most ambitious and radical project emerged. Announced by Frank as a “visual study of civilization,” it exposed characteristic aspects of US society during the Cold War in terms of patriotism, racism, religion, politics, consumerism, and leisure culture. If the artist had explored social patterns with a subjective gaze in earlier works, he now sharpened his approach: he took to spontaneously photographing ordinary motifs of high symbolic content, frequently without looking through the viewfinder of his 35 - mm camera , and reversed their meaning through his grim imagery.

Such patriotic motifs as flags are described as trivial; politicians are characterized as egomaniacal and narcissistic; the inhabitants appear lonely and isolated. Frank’s style developed in line with contemporary US - American art. Similarly, intuition and improvisation were central devices in Beat literature and Abstract Expressionism. Moreover, in the 1930s and 1940s the photographers of the Federal Security Administration (FSA) had already captured ma rginal groups of society in momentary pictures to formulate a visual critique of American society.

Les Américains/The Americans

In 1958, Robert Frank released eighty - three photographs from his Guggenheim trips as a book that first appeared with the French publisher Robert Delpire. In allusion to Henri Cartier - Bresson’s publication Les Européens, Delpire chose the title Les Américains. The following year the English edition The Americans was published by Grove Press. Both titles are considered incunabula of the artistic photo book genre. Robert Frank defined the format and layout, with a single photograph appearing on every right - hand page. He divided the book into four parts, each of which addressed themes of his personal view of America. As had already been the case with his book Black White and Things, the layout broke with the conventional, narrative form of a book, as the artist grouped the pictures according to thematic, formal, conceptual, and language - based criteria. In the French version, the photos were combined with texts criticizing America by such authors as William Faulkner, Simone de Beauvoir, and Walt Whitman against Frank’s will, which placed the pictures in a socio - documentary context. The American edition, on the other hand, was solely accompanied by an introductory text by Beat poet Jack Kerouac. Upon its appearance, The Americans met with fervent criticism. Frank’s perspective of the United States as a Swiss and thus as an outsider conflicted with the country’s self - portrayal and self - perception. In contemporary reviews, the photographs were described as documents of maliciousness and hopelessness, and Frank was identified as a morose man hating America. At the same time, the publication was greatly praised amongst professional circles and has received wide and lasting response since the 1960s.

Contact Sheets and Work Prints

The harvest of Robert Frank’s photographic travels through the United States took up 767 rolls of film. Relying on contact sheets, the artist examined the 27,000 negatives these rolls contained and picked one thousand pictures, which he developed as small - form at work prints. These were narrowed down further to a selection of just under one hundred final prints. The contact sheets and work prints allow us to reconstruct the genesis of The Americans and shed light on Frank’s working method. While the photographer sometimes achieved a satisfactory result with the first push on the camera button, he occasionally captured the same motif a number of times before he chose one of the pictures. The lack of definition and faulty exposure of many negatives leave no doubt bout Frank’s intuitive approach. The unceasing repetition of individual motifs evidences how methodically the artist proceeded in some cases. Before setting out, Frank had already defined such highly symbolic motifs as flags, cowboys, motorbikes, parades, and politicians, which he continued to photograph after the end of his travels to complete their range.

On Independence Day, the Fourth of July, he returned to Jay in the north of the state of New York, for example, to photograph a transparent flag.

Coney Island and From the Bus

Afraid of repeating himself and dissatisfied with the limited possibilities of the single image, Frank abandoned photography and turned his attention to film after the publication of The Americans.

Coney Island and From the Bus are two of his last groups of works before he began to pursue a career as a filmmaker. Coney Island captures the leisure and entertainment neighborhood in the eponymous borough of Brooklyn in New York City on Independence Day, the Fourth of July. Frank’s gloomy photographs emphasize the bleakness of the place and aspects of human solitude instead of rendering the joyful festivities and the patriotic attitude traditionally displayed on the national holiday. His focus on the predominantly Afro - American population reflects the artist’s disillusionment with racism, which he had been confronted with repeatedly when travelling the United States. Whereas Coney Island seamlessly follows in the vein of the pictorial language that characterizes The Americans, the serial conception of From the Bus clearlyanticipates Frank’s turn toward film. The series pictures passing people casually shot from a New York City bus. The representation of unspectacular moments, “unartistic” compositions, and photographing along a prede fined route already prefigure the conceptual photography of the 1960s.

Conversations in Vermont

After feature films like the beatnik piece Pull My Daisy (1959), Robert Frank shot a series of autobiographical essay films. In these films he often used his own photos to deal with his personal memories, family history, or attitude toward his work as an artist. In Conversations in Vermont (1969), we find Frank filming pictures from his cycles London, Paris, and The Americans as he seeks to fathom his role as a father and artist. Visiting his children, Andrea and Pablo, in the state of Vermont, he confronted them with his iconic photographs. Andrea and Pablo reacted evasively and were hardly interested in the pictures and their father’s past. This meeting led Frank to admit that he had pursued his career as an artist without showing consideration for his family.

Home Improvements

The video Home Improvements ( 1985) is one of Robert Frank’s autobiographical works in which he deals with his life in a diary - like manner. The melancholy piece revolves around Frank’s worries over his wife June Leaf and his son Pablo, who were in the hospital at the time. At some point, the film refers to photographs showing mainly Pablo and pictures from the series The Americans. He used these photographs to inquire into his past and the public perception of his work as an artist. For example, we see Frank filming a friend brutally drilling several holes through a batch of older prints. This act is to be read as a comment on a fierce litigation he conducted against a group of gallery owners in the early 1980s. He had sold the rights to his photographs to them in 1977 in order to fund h is films. When the gallery owners started turning the pictures to account against Frank’s intentions, he put up a struggle against the loss of control over his oeuvre and its commercialization going hand in hand with it. Though he finally succeeded, he found himself unable to trust in the art market from that time on.

The Return to Photography: Experimental Photo Montages/The Late Work

In the early 1970s, Robert Frank began to take photographs again. Single pictures gave way to experimental montages in which he combined pictures with words and sentence fragments. Now using a Polaroid instant camera, Frank exposed several negatives on the same paper or mounted photos next to one another. He also inscribed and scratched the negatives and prints. Both the photographer’s subjective comments and the montage technique were owed to the influence of his filmmaking. Pictures of his immediate surroundings lend expression to the artist’s world of inner emotions.

Through landscape impressions of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, where Frank has lived since the 1970s,

and For Andrea 1954 – 1974 visualize the artist’s emotions about the early death of his daughter, who died in a plane crash in 1974. His work also reflects the great strain under which the artist suffered due to his son Pablo’s progressing physical and mental illness and his death in 1994.

As he had done in his films, Frank, intent on venting his critical attitude toward his artistic past, incorporated pictures he had taken for The Americans in his new works. One example is the photograph of a priest on the banks of the Mississippi River, which had been published in The Americans. Collaborating with the Rolling Stones in the early 1970s, he used it for

the montage on the back cover for the group’s album Exile on Main Street. In the case of the photo work of the same name, for which Frank again fell back on the picture of the priest, he duplicated the photograph and combined it with a line from the song “Sweet Virginia,” to be found on the Rolling Stones’ album.

The work testifies to the use of older motifs in different contexts so typical of the artist’s late work.

The Lines of My Hand

Robert Frank’s book The Lines of My Hand came out in 1972. Originally published by Yugensha in Japan, its American edition was put out by Lustrum Press. The volume assembles pictures from all periods of the photographer’s production under subjective aspects. Like the photographs and films of that time, the personal arrangement of the pictures and their combination with diary - like texts serve as vehicles for the artist’s introspective self - reflection. The confrontation with his old pictures during his work on the book triggered a new return to photography.

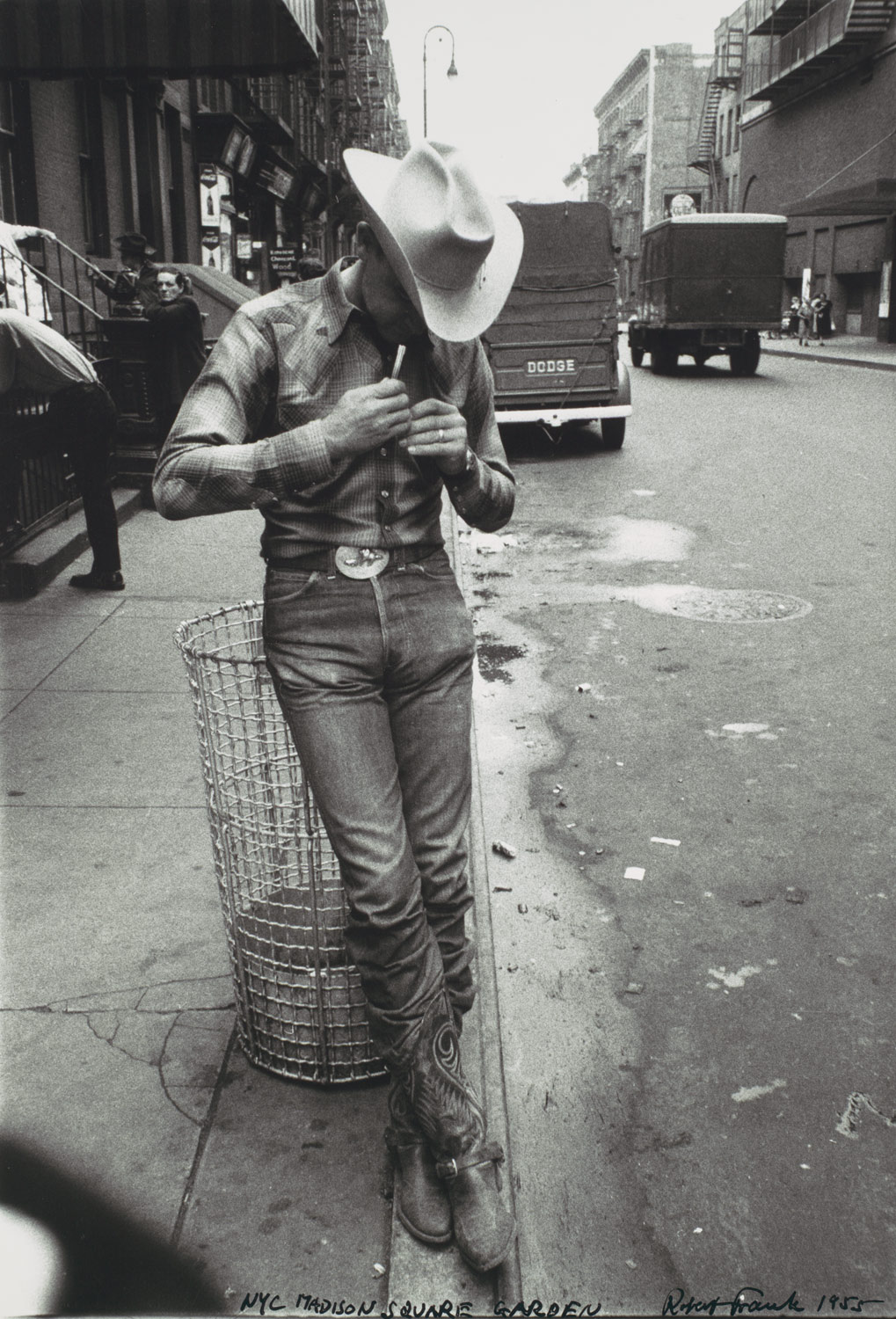

Robert Frank

Rodeo – New York City, 1955

Gelatin silver print

© Robert Frank, Fotostiftung Schweiz, Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, Bundesamt für Kultur (BAK), Bern

Robert Frank

Drugstore – Detroit, 1955

Gelatin silver print

© Robert Frank, The Albertina Museum, Vienna – Dauerleihgabe der Österreichischen Ludwig-Stiftung für Kunst und Wissenschaft

Robert Frank

San Francisco, 1956

Gelatin silver print

© Robert Frank, The Albertina Museum, Vienna – Dauerleihgabe der Österreichischen Ludwig-Stiftung für Kunst und Wissenschaft

Robert Frank

Los Angeles, 1955/56

Gelatin silver print

© Robert Frank, The Albertina Museum, Vienna – Dauerleihgabe der Österreichischen Ludwig-Stiftung für Kunst und Wissenschaft

Robert Frank

14th Street White Tower – New York City, 1948

Gelatin silver print

© Robert Frank, Sammlung Fotostiftung Schweiz, Schenkung des Künstlers

Robert Frank

Car Accident – U.S. 66 between Winslow and Flagstaff, Arizona, 1956

Gelatin silver print

© Robert Frank, The Albertina Museum, Vienna – Dauerleihgabe der Österreichischen Ludwig-Stiftung für Kunst und WissenschaftRobert Frank

Rodeo – Detroit, 1955

Gelatin silver print

© Robert Frank, The Albertina Museum, Vienna – Dauerleihgabe der Österreichischen Ludwig-Stiftung für Kunst und Wissenschaft

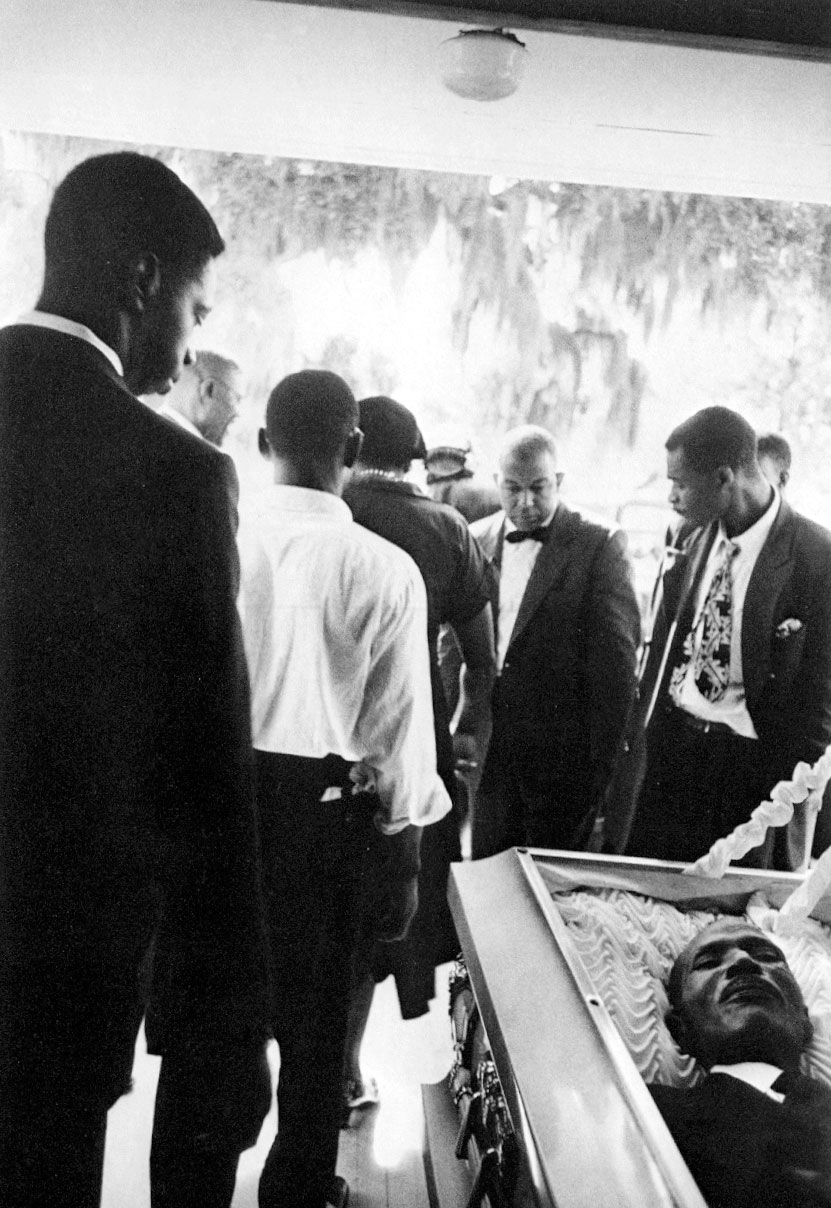

Robert Frank

Funeral – St. Helena, South Carolina, 1955

Gelatin silver print

© Robert Frank, The Albertina Museum, Vienna – Dauerleihgabe der Österreichischen Ludwig-Stiftung für Kunst und Wissenschaft

Robert Frank

Cafeteria – San Francisco, 1956

Gelatin silver print

© Robert Frank, The Albertina Museum, Vienna – Dauerleihgabe der Österreichischen Ludwig-Stiftung für Kunst und Wissenschaft

Read "Robert Frank: The Man Who Saw America" published in the New York Times in Summer 2015, written by Nicholas Dawidoff:

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/05/magazine/robert-franks-america.html

Considered one of the most influential figures in the history of photography – it was Jack Kerouc who first defined Frank as a genius – Frank found fame in the early 1960s with his ground-breaking book The Americans. The series offers a profound insight into the country’s cultural and social conditions and, despite initially perplexing critics due to its unorthodox style, soon became and still remains widely regarded as a pivotal work in 20th century art history.

Its origins can be traced to Frank’s time spent in Paris, and his visit to England and Wales in the 1950s. In Paris, where Frank spent two years in 1949 – 1950, he captured the city’s beauty, viewing its streets as a stage for human activity. As seen in this exhibition, these photographs of Paris taken during that time focus on lonesome, romantic places and people in the city, in particular on the flower sellers. In London, Frank photographed labourers and bankers alike, capturing the city’s spirit following World War II. On one level Frank’s view of London is gloomy, portraying lonely individuals emerging from the nightmare of their recent history, each alienated as they pass people of a different social class. However, his outlook is tempered by capturing the hopeful faces of the children living there. Frank’s camera becomes an extension of his eye, depicting individuals each with their own stories to tell.

In March 1953, inspired by Richard Llewelyn’s poignant 1939 novel How Green Was My Valley, Frank’s exploration of coal-stained Caerau in South Wales began. Wales at the time was isolated from Britain’s financial centre, with a different language and culture and for the most part inhabited by people who had lived there all their lives. Frank sought an isolated community with complex cultural traditions and a history of self–determination, and he found it in this small town where many people lived in impoverished conditions. Frank chose to create a photographic story focused on 53-year-old Ben James, who had worked as a miner since the age of 14, and lived with his family in a house with no running water. Frank was there at the start of a time of transition in the lives of the miners, when the rebuilding of the economy after the Second World War meant mines were being modernised and working conditions were to slowly improve. With permission from the Coal Board and the men themselves to follow and document their daily lives, Frank created a narrative story about James and his family that could be organised as a day in the miner’s life. The emotional complexity with which he treated his subject set a precedent for Frank’s later work, when he would go on to treat all his subjects with a similar poetic sensibility. When the photographs of James were first published in the 1955 issue of U.S. Camera Annual, Frank confessed “I could have followed a livelier and perhaps more colourful Welsh miner but I’m happy I decided to portray Ben James. When I said farewell to him I realised that no future story on any Welsh miner will look as this one does. I’m sure the new generation is essentially the same but I wonder if not having such hardships will make it easier for them.” Having set out to document the miners’ lives during this transitional period, Frank had ended up revealing their humanity from within. Unlike much of the work that picture magazines were publishing at the time, Frank’s documentation of Wales expressed more emotion and delved deeper into people’s inner lives, effectively breaking the rules of documentary photography at the time.

On 27 May 1953, just two months after Frank returned from Wales to USA, Edward Steichen’s Postwar European Photography exhibition opened at The Museum of Modern Art in New York and 22 of Frank’s photographs were shown, most taken in London and Wales. The images of bankers, beggars and miners filled one large wall, floor to ceiling. Within a matter of months, many of the same subjects would capture Frank’s attention in America and he would use the same methods he had refined and developed in Paris, London and Wales in the 1950s. Described by Lou Reed as “the great democratic”, Frank’s search for equality in Wales set the tone for the seminal pictures that became The Americans.

Robert Frank was born in 1924 in Zurich, Switzerland. From 1941 Frank embarked on a series of apprenticeships as a photographer’s assistant in his home country. Moving to New York in 1947, Frank was soon hired by Alexey Brodovtich as a fashion photographer for Harper’s Bazaar, which bought with it opportunity to travel. The United States made such an impression on Frank that, after receiving his first Guggenheim Fellowship in 1955, Frank embarked on his two-year trip across America. In 1959 Frank began making films and in 1972, documented the Rolling Stones on tour which is today probably his most well know film. Frank’s photography and films have been the subject of exhibitions worldwide since Edward Steichen first included Frank’s photographs in the 1950 group show 51 American Photographers at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Frank was given his first solo show by the Art Institute of Chicago in 1961 and others soon followed. More recent exhibitions include “Robert Frank: Storylines” at Tate Modern, London in 2004, “Looking In: Robert Frank’s The Americans” which opened at National Gallery of Art, Washington in 2009 and then travelled to San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Frank has received many honours and his work is now held in numerous collections worldwide including Art Institute of Chicago; Maison European de la Photographie, Paris, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Tate Modern, London, the Victoria and Albert Museum, London and Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. In 1990 the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., established the Robert Frank Collection. Numerous monographs of Frank’s work exist, including The Americans (1958, 1959), New York to Nova Scotia (1986), London/Wales (2003), to name a few. Robert Frank now lives in New York City.

Read "Robert Frank: The Man Who Saw America" published in the New York Times in Summer 2015, written by Nicholas Dawidoff:

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/05/magazine/robert-franks-america.html

Considered one of the most influential figures in the history of photography – it was Jack Kerouc who first defined Frank as a genius – Frank found fame in the early 1960s with his ground-breaking book The Americans. The series offers a profound insight into the country’s cultural and social conditions and, despite initially perplexing critics due to its unorthodox style, soon became and still remains widely regarded as a pivotal work in 20th century art history.

Tusuque, N.M., 1955, printed 1978

© Robert Frank

© Robert Frank

Its origins can be traced to Frank’s time spent in Paris, and his visit to England and Wales in the 1950s. In Paris, where Frank spent two years in 1949 – 1950, he captured the city’s beauty, viewing its streets as a stage for human activity. As seen in this exhibition, these photographs of Paris taken during that time focus on lonesome, romantic places and people in the city, in particular on the flower sellers. In London, Frank photographed labourers and bankers alike, capturing the city’s spirit following World War II. On one level Frank’s view of London is gloomy, portraying lonely individuals emerging from the nightmare of their recent history, each alienated as they pass people of a different social class. However, his outlook is tempered by capturing the hopeful faces of the children living there. Frank’s camera becomes an extension of his eye, depicting individuals each with their own stories to tell.

London, 1951

© Robert Frank

© Robert Frank

On 27 May 1953, just two months after Frank returned from Wales to USA, Edward Steichen’s Postwar European Photography exhibition opened at The Museum of Modern Art in New York and 22 of Frank’s photographs were shown, most taken in London and Wales. The images of bankers, beggars and miners filled one large wall, floor to ceiling. Within a matter of months, many of the same subjects would capture Frank’s attention in America and he would use the same methods he had refined and developed in Paris, London and Wales in the 1950s. Described by Lou Reed as “the great democratic”, Frank’s search for equality in Wales set the tone for the seminal pictures that became The Americans.

Robert Frank was born in 1924 in Zurich, Switzerland. From 1941 Frank embarked on a series of apprenticeships as a photographer’s assistant in his home country. Moving to New York in 1947, Frank was soon hired by Alexey Brodovtich as a fashion photographer for Harper’s Bazaar, which bought with it opportunity to travel. The United States made such an impression on Frank that, after receiving his first Guggenheim Fellowship in 1955, Frank embarked on his two-year trip across America. In 1959 Frank began making films and in 1972, documented the Rolling Stones on tour which is today probably his most well know film. Frank’s photography and films have been the subject of exhibitions worldwide since Edward Steichen first included Frank’s photographs in the 1950 group show 51 American Photographers at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Frank was given his first solo show by the Art Institute of Chicago in 1961 and others soon followed. More recent exhibitions include “Robert Frank: Storylines” at Tate Modern, London in 2004, “Looking In: Robert Frank’s The Americans” which opened at National Gallery of Art, Washington in 2009 and then travelled to San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Frank has received many honours and his work is now held in numerous collections worldwide including Art Institute of Chicago; Maison European de la Photographie, Paris, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Tate Modern, London, the Victoria and Albert Museum, London and Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. In 1990 the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., established the Robert Frank Collection. Numerous monographs of Frank’s work exist, including The Americans (1958, 1959), New York to Nova Scotia (1986), London/Wales (2003), to name a few. Robert Frank now lives in New York City.

No comments:

Post a Comment