Artist’s Biography

Irving Penn was born in 1917 in Plainfield, New Jersey. In 1934 he enrolled at the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art, where he studied design with Alexey Brodovitch.

In 1938 he began a career in New York as a graphic artist. Then, after a year painting in Mexico, he returned to New York City and began work at Vogue magazine, where Alexander Liberman was art director.

Liberman encouraged Penn to take his first color photograph, a still life that became the October 1, 1943, cover of Vogue, beginning a fruitful collaboration with the magazine that continues to this day. In addition to his editorial and fashion work for Vogue, Penn has photographed for other magazines and for a number of commercial clients in America and around the world.

He has published nine books of photographs: Moments Preserved (1960); Worlds in a Small Room (1974); Inventive Paris Clothes (1977); Flowers (1980); Passage (1991); Irving Penn Regards The Work of Issey Miyake (1999); Still Life (2001); Earthly Bodies (2002); A Notebook at Random (2004); and two books of drawings.

Penn's photographs are in the collections of major museums in America and throughout the world, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Moderna Museet in Stockholm, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which honored him with a retrospective exhibition in 1984. That exhibition was circulated to museums in twelve countries. In 1997, Penn made a major donation of prints and archival material to the Art Institute of Chicago. He made his gift of the Platinum Test Materials collages and 85 corresponding prints as well as archival material to the National Gallery of Art in 2002 and 2003.

Irving Penn, one of the 20th century's most influential photographers of fashion and the famous, whose signature blend of classical elegance and cool minimalism was recognizable to magazine readers and museum goers worldwide, died at the age of 92 in October, 2008.

A meticulous craftsman, Penn (born 1917) has experimented extensively with platinum/palladium printing since the early 1960s, transforming his celebrated photographs into independent works of art with remarkably subtle, rich tonal ranges and luxurious textures. In 2002 and 2003 Penn gave the National Gallery of Art 17 unique collages known as the Platinum Test Materials and 85 platinum/palladium prints as well as archival material. Spanning most of Penn’s innovative career from the 1940s to the late 1980s, this important collection represents all of Penn’s genres: from fashion photographs and still lifes to portraits of some of the 20th century’s most celebrated figures—Pablo Picasso, David Smith, and Colette, for example—and studies of anonymous individuals from around the world. Organized by the National Gallery of Art, the exhibition presents the collages and prints together for the first time.

| Irving Penn (American, 1917–2009) Rochas Mermaid Dress (Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn), Paris, 1950 Platinum-palladium print, 1980 19 ⅞ × 19 ¾ in. (50.5 × 50.2 cm) Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York © Condé Nast Publications, Inc. |

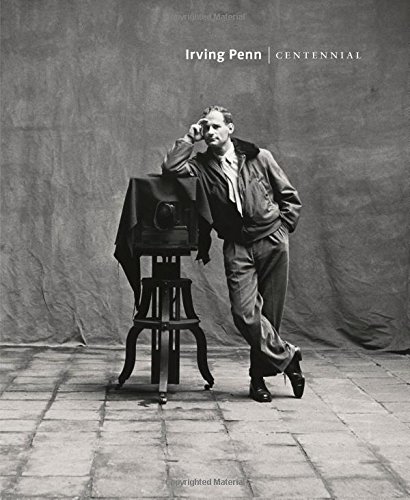

The Metropolitan Museum of Art will present a major retrospective of the photographs of Irving Penn to mark the centennial of the artist's birth. Over the course of his nearly 70-year career, Irving Penn (1917–2009) mastered a pared-down aesthetic of studio photography that is distinguished for its meticulous attention to composition, nuance, detail, and printmaking. Irving Penn: Centennial, opening April 24, 2017, will be the most comprehensive exhibition of the great American photographer's work to date and will include both masterpieces and hitherto unknown prints from all his major series.

Long celebrated for more than six decades of influential work at Vogue magazine, Penn was first and foremost a fashion photographer. His early photographs of couture are masterpieces that established a new standard for photographic renderings of style at mid-century, and he continued to record the cycles of fashions year after year in exquisite images characterized by striking shapes and formal brilliance. His rigorous modern compositions, minimal backgrounds, and diffused lighting were innovative and immensely influential. Yet Penn's photographs of fashion are merely the most salient of his specialties. He was a peerless portraitist, whose perceptions extended beyond the human face and figure to take in more complete codes of demeanor, adornment, and artifact. He was also blessed with an acute graphic intelligence and a sculptor's sensitivity to volumes in light, talents that served his superb nude studies and life-long explorations of still life.

Penn dealt with so many subjects throughout his long career that he is conventionally seen either with a single lens—as the portraitist, fashion photographer, or still life virtuoso—or as the master of all trades, the jeweler of journalists who could fine-tool anything. The exhibition at The Met will chart a different course, mapping the overall geography of the work and the relative importance of the subjects and campaigns the artist explored most creatively. Its organization largely follows the pattern of his development so that the structure of the work, its internal coherence, and the tenor of the times of the artist's experience all become evident.

The exhibition will most thoroughly explore the following series: street signs, including examples of early work in New York, the American South, and Mexico; fashion and style, with many classic photographs of Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn, the former dancer who became the first supermodel as well as the artist's wife; portraits of indigenous people in Cuzco, Peru; the Small Trades portraits of urban laborers; portraits of beloved cultural figures from Truman Capote, Joe Louis, Picasso, and Colette to Alvin Ailey, Ingmar Bergman, and Joan Didion; the infamous cigarette still lifes; portraits of the fabulously dressed citizens of Dahomey (Benin), New Guinea, and Morocco; the late "Morandi" still lifes; voluptuous nudes; and glorious color studies of flowers.

These subjects chart the artist's path through the demands of the cultural journal, the changes in fashion itself and in editorial approach, the fortunes of the picture press in the age of television, the requirements of an artistic inner voice in a commercial world, the moral condition of the American conscience during the Vietnam War era, the growth of photography as a fine art in the 1970s and 1980s, and personal intimations of mortality. All these strands of meaning are embedded in the images—a web of deep and complex ideas belied by the seeming forthrightness of what is represented.

Penn generally worked in a studio or in a traveling tent that served the same purpose, and favored a simple background of white or light gray tones. His preferred backdrop was made from an old theater curtain found in Paris that had been softly painted with diffused gray clouds. This backdrop followed Penn from studio to studio; a companion of over 60 years, it will be displayed in one of the Museum's galleries among celebrated portraits it helped create. Other highlights of the exhibition include newly unearthed footage of the photographer at work in his tent in Morocco; issues of Vogue magazine illustrating the original use of the photographs and, in some cases, to demonstrate the difference between those brilliantly colored, journalistic presentations and Penn's later reconsidered reuse of the imagery; and several of Penn's drawings shown near similar still life photographs.

Exhibition Credits

Irving Penn: Centennial is co-curated by Maria Morris Hambourg, independent curator and the founding curator of The Met's Department of Photographs, and Jeff L. Rosenheim, Joyce Frank Menschel Curator in Charge of the Department of Photographs at The Met.

Catalogue

The exhibition is accompanied by a 372-page book with 365 illustrations, including full-page reproductions of all the photographs exhibited, by Maria Morris Hambourg and Jeff L. Rosenheim. A probing introduction to the artist, his concerns, and the evolution of his work is provided by Hambourg, followed by lively in-depth studies of the central themes and episodes of his career, an illustrated chronology, and notes on Penn's printing by Hambourg, Rosenheim, and guest authors Alexandra Dennett, Philippe Garner, Adam Kirsch, Harald E.L. Prins, and Vasilios Zatse.

Irving Penn (American, 1917–2009), Nude No. 72, New York, 1949–50. Gelatin silver print 15 ⅝ × 14 ¾ in. (39.7 × 37.5 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the artist, 2002 © The Irving Penn Foundation.

- Irving Penn (American, 1917–2009)

After-Dinner Games, New York, 1947

Dye transfer print, 1985

22 ¼ × 18 ⅛ in. (56.5 × 46 cm)

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation to

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© Condé Nast Publications, Inc. - Irving Penn (American, 1917–2009)

Cigarette No. 37, New York, 1972

Platinum-palladium print, 1975

23 ½ × 17 ⅜ in. (59.7 × 44.1 cm)

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation to

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© The Irving Penn Foundation - Irving Penn (American, 1917–2009)

Cuzco Children, 1948

Platinum-palladium print, 1968

19 ½ × 19 ⅞ in. (49.5 × 50.5 cm)

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation to

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© Condé Nast Publications, Inc. - Irving Penn (American, 1917–2009)

Fishmonger, London, 1950

Platinum-palladium print, 1976

19 ¾ × 14 ⅞ in. (50.2 × 37.8 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Purchase, The Lauder Foundation and The Irving Penn Foundation Gifts, 2014

© Condé Nast Publications, Ltd. - Irving Penn (American, 1917–2009)

Marlene Dietrich, New York, 1948

Gelatin silver print, 2000

10 × 8 1/8 in. (25.4 × 20.6 cm)

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation to

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© The Irving Penn Foundation - Irving Penn (American, 1917–2009)

Mouth (for L’Oréal), New York, 1986

Dye transfer print

18 ¾ × 18 ⅜ in. (47.6 × 46.7 cm).

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation to

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© The Irving Penn Foundation - Irving Penn (American, 1917–2009)

Naomi Sims in Scarf, New York, ca. 1969

Gelatin silver print, 1985

10 ½ × 10 ⅜ in. (26.7 × 26.4 cm)

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation to

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© The Irving Penn Foundation - Irving Penn (American, 1917–2009)

Pablo Picasso at La Californie, Cannes, 1957

Platinum-palladium print, 1985

18 ⅝ × 18 ⅝ in. (47.3 × 47.3 cm)

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation to

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© The Irving Penn Foundation - Irving Penn (American, 1917–2009)

Tribesman with Nose Disc, New Guinea, 1970

Gelatin silver print, 2002

15 ½ × 15 ⅜ in. (39.4 × 39.1 cm)

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation to

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© The Irving Penn Foundation - Irving Penn (American, 1917–2009)

Truman Capote, New York, 1948

Platinum-palladium print, 1968

15 7/8 × 15 3/8 in. (40.3 × 39.1 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith

Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1986

© The Irving Penn Foundation

Irving Penn (American, 1917–2009)Ingmar Bergman, Stockholm, 1964Gelatin silver print, 199215 ⅛ × 15 in. (38.4 × 38.1 cm)The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New YorkPromised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation© The Irving Penn Foundation

Irving Penn (American, 1917–2009)Girl Drinking (Mary Jane Russell), New York, 1949Gelatin silver print, 200020 ½ × 19 ⅜ in.(52.1 × 49.2 cm)The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New YorkPromised Gift of TheIrving Penn Foundation© Condé Nast

Irving Penn (American, 1917–2009)Glove and Shoe, New York, 1947Gelatin silver print9 ⅝ × 7 ¾ in. (24.4 × 19.7 cm)The MetropolitanMuseum of Art, New YorkPromised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation© Condé NastIrving Penn (American, 1917–2009)Three Dahomey Girls, One Reclining, 1967Platinum-palladium print, 198019 ¾ × 19 ¾ in. (50.2 × 50.2 cm)The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New YorkPromised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation© The Irving Penn FoundationIrving Penn (American, 1917–2009)Ungaro Bride Body Sculpture (Marisa Berenson), Paris, 1969Gelatin silver print, 198512 × 9 ⅜ in. (30.5 × 23.8 cm)The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New YorkPromised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation© Condé NastIrving Penn (American, 1917–2009)Ta Tooin (The Bowery), New York, ca. 1939Gelatin silver print9 ½ × 7 ½ in. (24.1 × 19.1 cm)The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New YorkPromised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation© The Irving Penn FoundationIrving Penn (American, 1917–2009)Three Asaro Mud Men, New Guinea, 1970Platinum-palladium print, 197620 ⅛ × 19 ½ in. (51.1 × 49.5 cm)The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New YorkPromised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation© The Irving Penn Foundation

"Igor Stravinsky, New York , 1948"

"Jean Cocteau, Paris, 1948"

Portraits: Widely celebrated for his portraits, Penn adeptly utilizes formal design elements to reveal the character and personality of his subjects. The exhibition included many of Penn’s iconic portraits, including

Colette, Paris (1951; platinum/palladium print, 1976), and Steinberg in Nose Mask, New York (1966; platinum/ palladium print, 1976). In the 1940s, Penn positioned his sitters in a small corner space made of two studio flats, a device of his own creation; one example on view was

Marcel Duchamp, New York (1948; platinum/palladium print, 1979). Penn developed a more direct approach by the late 1950s, photographing subjects at close range, such as Picasso at La Californie, Cannes, France (1957; platinum/palladium print, 1974).

Fashion Studies: Examples of Penn’s fashion studies, a steady part of his editorial assignments from Vogue for more than 50 years, was also on view as part of the collection. Penn came to fame immediately after World War II by presenting his models in simple settings, free from the theatricality that had characterized earlier fashion photographs. Many of the works were of his wife, his favorite model, seen in

Ethnographic Subjects: In 1948, after a fashion project in Lima, Peru, Penn flew to the town of Cuzco in the Andes. The Quechuan Indians he found there so captivated him that on impulse he rented the local photographer’s studio. The exhibition included

Cuzco Children (1948; platinum/palladium print, 1978) among the works on view from that famous encounter. Fifteen years later, Penn would again take up ethnographic subjects, photographing such works as

Platinum Test Materials Collages: The exhibition concluded with 12 Platinum Test Materials collages, which draw upon all of Penn’s genres, and make provocative associations between the works. When Penn made his platinum prints, he often used test strips, positioned to capture a photograph’s most relevant details and tonal range, instead of exposing full sheets of paper. In the late 1980s when he re-examined some of these strips, he was struck by their aesthetic qualities and attached several of them to large sheets of paper. By mixing together images from throughout his career, these collages reveal the diversity of his work and the unexpected juxtapositions between fashion and art, Western and non-Western ideals of beauty and adornment, and Penn’s personal and commercial work.

Still Life

A still life is a representation of people. —Irving Penn In still life—his first and perhaps deepest love in photography—Penn established a notable discipline of rigor and compression that stood him in good stead for his long career with the camera. Still lifes were among his earliest assignments after joining Vogue in 1943. When composing these pictures he played the role of storyteller but left out the human protagonists. All that remains are their traces—an alluring smear of lipstick on a brandy glass, a burnt match. Penn constructed these (and all of his) photographs through a bravura act of reduction, challenging the viewer to apprehend their internal order and read them for signs of life.

Theatre Accident, New York, 1947 Dye transfer print, 1984

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Still Life with Watermelon, New York, 1947 Dye transfer print, 1985 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Salad Ingredients, New York, 1947 Dye transfer print, 1984 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Early Street Photographs

Theatre Accident, New York, 1947 Dye transfer print, 1984

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Still Life with Watermelon, New York, 1947 Dye transfer print, 1985 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Salad Ingredients, New York, 1947 Dye transfer print, 1984 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Early Street Photographs

Penn acquired his first camera—a twin-lens-reflex, 2¼-inch-square-format Rolleiflex—in 1938 while working as an assistant to Alexey Brodovitch, the legendary graphic designer and art director at Harper’s Bazaar. Penn’s earliest photographs are studies of nineteenth-century shopfronts, hand-lettered advertisements, and street signs in Philadelphia and New York. With their visual clarity and vernacular content, these pictures reflect the subject matter of Depression-era, documentary-style photography. Frequently, Penn focused in close to his subject when framing the image in the camera and then cropped it more extremely in his finished print.

Penn continued this style of picture-making on a short trip through the American South in 1941 and during the following year, which he spent painting and photographing in Mexico.

O’Sullivan’s Heels, New York, ca. 1939 Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Union Bar Window, American South, 1941 Gelatin silver print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Penn continued this style of picture-making on a short trip through the American South in 1941 and during the following year, which he spent painting and photographing in Mexico.

O’Sullivan’s Heels, New York, ca. 1939 Gelatin silver printPromised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Union Bar Window, American South, 1941 Gelatin silver print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

In late November 1948 Vogue sent Penn to Lima, Peru, for his first fashion assignment on location. After completing the sessions with Jean Patchett, he traveled alone to Cuzco, the splendid city high in the Andes. Penn quickly found a local photographer’s daylight studio to rent and produced, in three days, hundreds of portraits of residents and visitors from nearby villages, all wearing their traditional woolen clothing. The photographs reveal a couturier’s instinctive grasp of a garment’s weight, pattern, and texture and a stage director’s knack for posing subjects. The Cuzco series also established the fundamental visual and psychological principles behind the portraits Penn would make in distant corners of the world over the next twenty-five years. Although virtually all of the Cuzco photographs that Penn later printedare in black and white (both gelatin silver and platinum-palladium prints), he used color transparency film for much of his work in Peru.

Penn photographed both residents and visitors who came to the city from nearby villages with goods to sell or barter at the Christmastime fiestas. Many arrived at the studio to sit for their annual family portraits. Penn later recalled that they “found me instead of him [the local photographer] waiting for them, and instead of paying me for the pictures it was I who paid them for posing.”

Young mothers arrived at Penn’s rented studio with their newborns strapped in little hammocks on their backs; shepherds and porters came dressed in colorful, striped ponchos and woolen capes; and street vendors from near and far showed up with their wares, including straw hats, newspapers, and fresh eggs from the valleys far below the city. Penn posed these sitters with his distilled awareness of the poetics of available light and his sense of how to delicately tilt a head in order to strengthen a chin, shadow an ear, or animate the eyes.

Street Vendor Wearing Many Hats, Cuzco, 1948 Irving Penn: Centennial Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationThe woman in this photograph poses in an ensemble typically worn during mourning rites.Sitting Enga Woman, New Guinea, 1970 Gelatin silver print, 1984Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationEnga Tribesman, New Guinea, 1970 Gelatin silver print, 1984Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationWoman with Three Tribesmen, New Guinea, 1970Gelatin silver print, 1984Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationMan with Pink Face, New Guinea, 1970 Silver dye bleach print, 1993Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationAlthough Penn worked in both color and black and white when traveling the far corners of the globe, he produced almost no color prints of the pictures. That visual experience was left to the printed pages of Vogue,which published them from 1967 to 1971 (see case nearby). Penn made this trial print of a New Guinea man two decades later, by which time doubts about color photography’s capacities as an art form had evaporated. Penn evidently preferred the black-and-white medium, however, and did not make further color trials.

Morocco, 1971

If Cuzco was the start of Penn’s project to photograph remote peoples of the world in situ, then Morocco was the end of the journey. For this last expedition, Penn set up his tent in the town square of Guelmin, a southern city home to an ancient camel market and known as the “Gateway to the Desert.” Penn wrote that he invited the guedradancers to pose: “Those chosen sat, eyes fixed on the lens, enjoying the camera’s scrutiny yet themselves impenetrable.” After the trip, Penn began printing photographs from his travels for his book Worlds in a Small Room(1974).Among the Moroccan subjects, he selected several images that would speak eloquently in black and white. Veiled in their burkas and seated in rocklike immobility, the figures are enigmatic. Despite the challenging, wind-whipped conditions, Penn was able to extract mesmeric monuments of stillness, a remarkable demonstration of patience and expertise in visualizing a desired outcome.Woman with Three Loaves, Morocco, 1971 Gelatin silverprint, 1990Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationTwo Guedras, Morocco, 1971 Platinum-palladium print, 1977 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationFour Guedras, Morocco, 1971Platinum-palladium print, 1985Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationTwo Women in Black with Bread, Morocco, 1971Platinum-palladium print, 1986Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Dahomey, 1967

Penn visited the newly independent Republic of Dahomey, present-day Benin, shortly after photo-graphing an African art exhibition in Paris in 1966. It was for this and subsequent trips to Africa and the Pacific that he designed his portable studio, made of an aluminum skeleton covered by a special windowed nylon tent. His first sitters in Dahomey were children and young women living in the lagoon town of Ganvié, known to Westerners as the “Venice of Africa.” The trip to Dahomey was inspired by widely circulated photographs of legendary female warriors who had been infamously exhibited at world’s fairs in the nineteenth century. Seen within this context, Penn’s photographs may evoke unsettling narratives of colonial history. They reveal a dichotomy of wills, a tension between the self-possession and occasional defiance of the sitters and the artist’s overt direction of their postures.

Library Time Capsules

The portraits and photographs of style in this room range in date from the 1960s to the first decade of the twenty-first century. The expressions of sixties modernity—such as model Marisa Berenson in a brazen bridal outfit and author Tom Wolfe’s BeauBrummel flair—embody the swinging “youthquake” years. The lighter tone of these images yields, in works from more recent decades, to nostalgic fantasies and suggestions of lost innocence and futile vanity. While Penn’s sense of beauty had always included the inevitability of decay, the death of his wife (in 1992) and his own advancing years affected his perspective, turning his late fashion photography into a brilliant mirror of life’s transience.

Late Still Life

Penn managed to stay creative throughout his sixty-six years at Vogue because the editorial demands continuously evolved and because he engaged in personally nourishing side projects exploring still life, his first love.

Between 1975 and 2007 Penn produced four major series: Street Material, Archaeology, Vessels, and Underfoot. They are compositions of old bottles and vases, and of detritus—gutter rubbish, metal parts, rags, bones, and decaying fruit. In his off-hours, Penn often sketched or painted the same objects (see case nearby).

Like assembling a jigsaw puzzle, but in three dimensions, Penn’s still-life habit was a form of creative meditation. Engrossed with the materials, he considered the imaginative realms residing in the life of shoe leather, a fissured crock, or a flower petal. As sensitive to the charge emitted by objects as he was to the spark from individuals, Penn listened to their messages and photographed them singly or arranged in conversations, as human surrogates. These assemblages were then disassembled and painstakingly rearranged to form other constellations. Pictured are moments of rest in the ongoing flow of Penn’s active mind; they make permanent a cycle of constant change and offer further proof of the artist’s exceptional, lifelong fecundity.

Young mothers arrived at Penn’s rented studio with their newborns strapped in little hammocks on their backs; shepherds and porters came dressed in colorful, striped ponchos and woolen capes; and street vendors from near and far showed up with their wares, including straw hats, newspapers, and fresh eggs from the valleys far below the city. Penn posed these sitters with his distilled awareness of the poetics of available light and his sense of how to delicately tilt a head in order to strengthen a chin, shadow an ear, or animate the eyes.

Street Vendor Wearing Many Hats, Cuzco, 1948 Irving Penn: Centennial Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationThe woman in this photograph poses in an ensemble typically worn during mourning rites.Sitting Enga Woman, New Guinea, 1970 Gelatin silver print, 1984Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationEnga Tribesman, New Guinea, 1970 Gelatin silver print, 1984Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationWoman with Three Tribesmen, New Guinea, 1970Gelatin silver print, 1984Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationMan with Pink Face, New Guinea, 1970 Silver dye bleach print, 1993Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationAlthough Penn worked in both color and black and white when traveling the far corners of the globe, he produced almost no color prints of the pictures. That visual experience was left to the printed pages of Vogue,which published them from 1967 to 1971 (see case nearby). Penn made this trial print of a New Guinea man two decades later, by which time doubts about color photography’s capacities as an art form had evaporated. Penn evidently preferred the black-and-white medium, however, and did not make further color trials.

Morocco, 1971

If Cuzco was the start of Penn’s project to photograph remote peoples of the world in situ, then Morocco was the end of the journey. For this last expedition, Penn set up his tent in the town square of Guelmin, a southern city home to an ancient camel market and known as the “Gateway to the Desert.” Penn wrote that he invited the guedradancers to pose: “Those chosen sat, eyes fixed on the lens, enjoying the camera’s scrutiny yet themselves impenetrable.” After the trip, Penn began printing photographs from his travels for his book Worlds in a Small Room(1974).Among the Moroccan subjects, he selected several images that would speak eloquently in black and white. Veiled in their burkas and seated in rocklike immobility, the figures are enigmatic. Despite the challenging, wind-whipped conditions, Penn was able to extract mesmeric monuments of stillness, a remarkable demonstration of patience and expertise in visualizing a desired outcome.Woman with Three Loaves, Morocco, 1971 Gelatin silverprint, 1990Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationTwo Guedras, Morocco, 1971 Platinum-palladium print, 1977 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationFour Guedras, Morocco, 1971Platinum-palladium print, 1985Promised Gift of The Irving Penn FoundationTwo Women in Black with Bread, Morocco, 1971Platinum-palladium print, 1986Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Dahomey, 1967

Penn visited the newly independent Republic of Dahomey, present-day Benin, shortly after photo-graphing an African art exhibition in Paris in 1966. It was for this and subsequent trips to Africa and the Pacific that he designed his portable studio, made of an aluminum skeleton covered by a special windowed nylon tent. His first sitters in Dahomey were children and young women living in the lagoon town of Ganvié, known to Westerners as the “Venice of Africa.” The trip to Dahomey was inspired by widely circulated photographs of legendary female warriors who had been infamously exhibited at world’s fairs in the nineteenth century. Seen within this context, Penn’s photographs may evoke unsettling narratives of colonial history. They reveal a dichotomy of wills, a tension between the self-possession and occasional defiance of the sitters and the artist’s overt direction of their postures.

Library Time Capsules

The portraits and photographs of style in this room range in date from the 1960s to the first decade of the twenty-first century. The expressions of sixties modernity—such as model Marisa Berenson in a brazen bridal outfit and author Tom Wolfe’s BeauBrummel flair—embody the swinging “youthquake” years. The lighter tone of these images yields, in works from more recent decades, to nostalgic fantasies and suggestions of lost innocence and futile vanity. While Penn’s sense of beauty had always included the inevitability of decay, the death of his wife (in 1992) and his own advancing years affected his perspective, turning his late fashion photography into a brilliant mirror of life’s transience.

Late Still Life

Penn managed to stay creative throughout his sixty-six years at Vogue because the editorial demands continuously evolved and because he engaged in personally nourishing side projects exploring still life, his first love.

Between 1975 and 2007 Penn produced four major series: Street Material, Archaeology, Vessels, and Underfoot. They are compositions of old bottles and vases, and of detritus—gutter rubbish, metal parts, rags, bones, and decaying fruit. In his off-hours, Penn often sketched or painted the same objects (see case nearby).

Like assembling a jigsaw puzzle, but in three dimensions, Penn’s still-life habit was a form of creative meditation. Engrossed with the materials, he considered the imaginative realms residing in the life of shoe leather, a fissured crock, or a flower petal. As sensitive to the charge emitted by objects as he was to the spark from individuals, Penn listened to their messages and photographed them singly or arranged in conversations, as human surrogates. These assemblages were then disassembled and painstakingly rearranged to form other constellations. Pictured are moments of rest in the ongoing flow of Penn’s active mind; they make permanent a cycle of constant change and offer further proof of the artist’s exceptional, lifelong fecundity.

In The 1960s Vogue asked Penn to photograph flowers, a subject that had not attracted him previously but became a passion for The duration of The commission. He wrote: “My preference is for flowers considerably after They have passed that point of perfection, when They have already begun spotting and browning and twisting on Their way back to The earth.”

The images were published in special Christmas issues from 1967 to 1973.

The images were published in special Christmas issues from 1967 to 1973.

Three Poppies ‘Arab Chief’, New York, 1969 Dye transfer print, 1992 Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Peony ‘Silver Dawn’, New York, 2006 Inkjet print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Underfoot IX, New York, 2000Gelatin silver print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Cup Face, New York, 1975 Platinum-palladium print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Mud Glove, New York, 1975 Platinum-palladium print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Camel Pack, New York, 1975 Platinum-palladium printPurchase, Nancy and Edwin Marks Gift, 1990 (1990.1000)Deli Package, New York, 1975 Platinum-palladium print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Cup, New York, 1975 Platinum-palladium print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Parade, New York, 1980 Platinum-palladium print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Still Life with Shoe, New York, 1980 Platinum-palladium print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Three Steel Blocks, New York, 1980 Platinum-palladium print Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

Still Life of Nine Pieces, New York, 2005 Inkjet printing, watercolor, and gum arabic on paper The Irving Penn Foundation

IRVING PENN QUOTES

“I myself have always stood in awe of the camera.I recognize it for the instrument that it is, part Stradivarius, part scalpel.”

“I don’t think I was overawed by the subjects. I thought we were in the same boat.”

“A beautiful print is a thing in itself.”

“The daylight . . . is the light of Paris, the light of painters.It seems to fall as a caress.”

“Photography is just the present state of man’s visual history.”

“To me personally,photography is a way to overcome mortality.”

No comments:

Post a Comment