Evans was deeply moved by two major European photographers of the first decades of the 20th century—Eugène Atget and August Sander—whose pictorial ideas were straightforward and quiet in spirit. Modern European literature was equally important to Evans, particularly the writing of French poet Charles Baudelaire, whose work celebrated ordinary life in the streets, and Gustave Flaubert, who emphasized objectivity and the non-appearance of the author in artistic expression. “Depth of Field” examines how Evans’ early exposure to these European creative ideals enabled him to recognize the aesthetic possibilities of capturing everyday life and landscapes in the United States.

After returning to the United States, Evans began to realize that the artistic material he was looking for was right in front of him, in the symbols and faceless architecture of the commercial world, the traces of everyday life found in cheap cafés and small-town streets and the widespread deprivations of the Great Depression.

By the 1930s Evans had developed a singular approach to image making that drew upon a concise narrative structure associated with literature and placed him on the path of becoming one of the world’s most important photographers. His precise and lyrical images of modern America in the making would frame the development of documentary photography in Europe and North America and serve as a significant point of orientation for numerous artists who came after him, including Diane Arbus, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Lee Friedlander, Robert Frank and Helen Levitt, among many others.

Organized chronologically, the retrospective begins with early work from the late 1920s, including some of Evans’ lesser-known projects, such as the Brooklyn Bridge, The Crime of Cuba and Antebellum Architecture, which will be presented together for the first time as discrete photographic essays. The exhibition then moves forward in time to the indelible images Evans made for the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression in the American South, the covert views he created in the subway system of New York in the late 1930s and early 1940s, the little-studied work he produced over his two decades as a staff photographer at Fortune magazine, to the often- overlooked Polaroid images Evans’ made toward the end of his career.

“Stare. It is the way to educate your eye, and more. Stare, pry, listen, eavesdrop. Die knowing something. You are not here long.” – Walker Evans

In the same year, three of his Brooklyn Bridge photographs were published with Hart Crane’s epic poem, “The Bridge.”

Walker Evans, Main Street, Saratoga Springs,

New York, 1931. Gelatin silver print. Lent by Elizabeth and Robert J. Fisher, MBA ’80.

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Walker Evans, Broadway, 1930. Gelatin silver print.

Lent by Elizabeth and Robert J. Fisher, MBA ’80.

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Accompanying the exhibition is a comprehensive and extensively illustrated publication that investigates the trans-Atlantic roots of Evans’ practice and his development of a compellingly lyrical documentary style. The book examines in detail the complex development of Evans’ oeuvre from his early street photography, to his iconic photographs of the Great Depression to his later embrace of colour photography. Over 400 pages, the hardcover publication features essays by John T. Hill, Heinz Liesbrock, Jerry L. Thompson, Alan Trachtenberg and Thomas Weski and features extensive illustrations ranging from the artist’s earliest images taken with a vest pocket camera to his final Polaroid photographs of the 1970s.

Walker Evans (1903-1975). People in Downtown Havana, 1933. Gelatin silver print. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Lincoln Kirstein, 1952, 52.562.7. © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In this wide-ranging exhibition, some 60 photographs by Evans were organized into eight groups, each devoted to a single dimension of his work. Each group is presented together with works by other artists-- mostly photographers, but also painters, sculptors, printmakers, and one architect--that anticipate, extend, or otherwise resonate with the given dimension of Evans's art. The exhibition thus employs tradition as a sounding board to amplify salient aspects of Evans's work and adopts his photography as a lens through which to explore the unfolding of artistic tradition.

Among the 70 artists represented in this exhibition of nearly 200 works were Robert Adams, Diane Arbus, Eugène Atget, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Harry Callahan, Stuart Davis, Philip-Lorca diCorcia, William Eggleston, Louis Faurer, Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander, Robert Gober, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Jan Groover, Andreas Gursky, Edward Hopper, Russell Lee, Roy Lichtenstein, Wright Morris, Robert Rauschenberg, Edward Ruscha, August Sander, Michael Schmidt, Cindy Sherman, Stephen Shore, Thomas Struth, Robert Venturi, Andy Warhol, Edward Weston, and Marion Post Wolcott.

The Museum of Modern Art began to acquire Evans's photographs in the early 1930s, not long after he began to make them, and thereafter enjoyed a close relationship with the artist throughout his life. The Museum's first one-person photography exhibition, in 1933, was Walker Evans: Photographs of Nineteenth-Century Houses, organized by Lincoln Kirstein. Five years later, MoMA exhibited Walker Evans: American Photographs and published the landmark book by the same title, with an afterword by Kirstein. In 1966 the Museum mounted the first showing of Evans's subway portraits of 1938-41 in the exhibition Walker Evans: Subway Photographs, and in 1971 it presented Walker Evans, the first major retrospective of the artist's work, organized by John Szarkowski. In 1988 the Museum issued a fiftieth-anniversary edition of American Photographs, accompanied by a touring exhibition.

Evans produced his most important work in the 1930s, much of it for the government agency now best known as the Farm Security Administration. But he had formed his outlook and style before the hard times settled in, and he approached his FSA job as a subsidized freedom to continue his work. Although Evans's photographs are habitually celebrated as documents of the Great Depression, Walker Evans & Company aimed to show that his restless interrogation of American society ranged far beyond the troubles of the Depression and continued to reverberate long after the 1930s. A good deal of FSA photography was modeled on Evans's dry, factual style, but his richest creative influence began to unfold after World War II, when his example of skeptical engagement with the contemporary scene proved invaluable to a diverse roster of younger photographers, beginning with Frank, Friedlander, and Arbus. In the 1960s and later, as the leaders of the Pop Art movement and its successors reinvigorated American painting and sculpture by embracing the everyday world, they demonstrated that both Evans's vernacular iconography--car culture, billboards and advertising, the movies, junk--and his indivisible alloy of ironic detachment and open affection were not time-bound relics of the 1930s but essential resources of contemporary art. So, too, was his nimble approach to photography as transparent fact, potent symbol, and medium of recycled replication.

The eight groupings that comprised the exhibition may be summarized as follows:

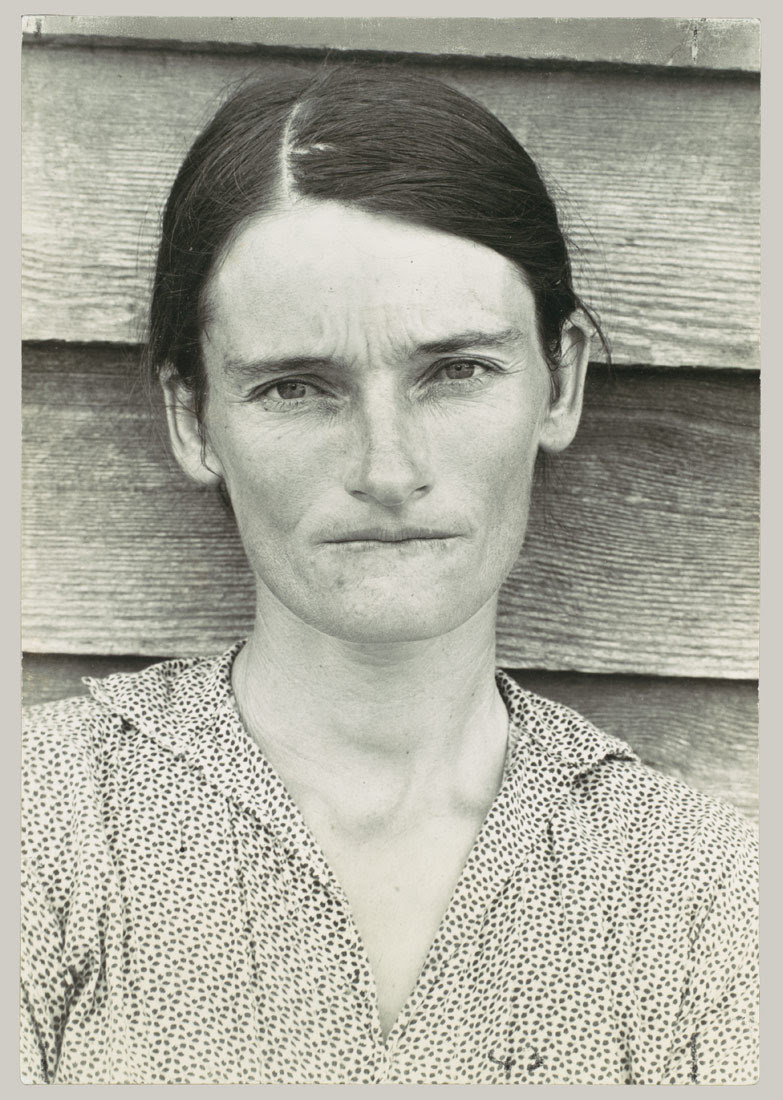

- Evans modeled his seemingly impersonal style on the sober clarity of American vernacular photography, but his ambition to draw an indelible picture of contemporary civilization--of the conflicted present understood as a collective inheritance from the past--owed still more to the work of two European predecessors, August Sander and Eugène Atget, who had shown that photography could creatively map the structure of a society. Just as

Sander's Peasant Woman (1914)

represents the bedrock of German culture,

Evans's Alabama Cotton Tenant Farmer Wife (1936)

is not a Depression victim to be pitied but a powerful exemplar of American honesty and grit.

- Evans's outline of an authentic American tradition composed of indigenous architecture and artifacts is easily misconstrued as nostalgic, but he was drawn by the new as well as the old. His image of American history may be described as a study of the incomplete industrial present in the process of supplanting the unfinished agrarian past.

Evans elected the automobile as an icon of our times--an embodiment of the American paradox by which mass production brought a new chance of personal freedom and mobility. Cars were still quite new in 1930, and most modernists pictured them as shining avatars of progress. In

Evans's Joe's Auto Graveyard, Pennsylvania (1936)

the cars form a landscape of waste and decay. His prescience in recognizing car culture as essential, symbolic material of modern America is seconded in the exhibition by such works as

Weston's Wrecked Car, Crescent Beach (1939),

Frank's Covered Car, Long Beach, California (1955-56), and Rauschenberg's First Landing Jump (1961).

- Although Evans's core aesthetic is rightly identified with the rectitude and precision of large-camera photography, he was among the first Americans to adopt the enthusiasm for small, handheld cameras that swept Europe in the 1920s. In fact, his earliest lasting pictures, such as

42nd Street (1929),

are small-camera studies of city characters--sharp observations of social types, which broaden his otherwise largely unpeopled image of American civilization. After World War II, the handcamera triumphed in America as advanced photographers pursued an increasingly complex image of the theater of the street. Nevertheless, many small-camera pictures of the period, such as

Arbus's Teenage Couple on Hudson Street, New York City (1963), are devoid of narrative incident. As in Evans's pictures, the main event is a static encounter between the photographer and one or more social beings, about whom we know nothing except what we see.

- While Evans photographed a variety of building exteriors--churches, banks, schools, and factories--most of his photographs of interiors were of homes. Pictures such as

Bed and Stove, Truro, Massachusetts (1931)

are marked by the same archaeological scrutiny that Evans regularly applied to the exterior. Despite the usual absence of the occupant, however, the interiors are dense with allusion to the passions and tribulations of individual lives. Eggleston's three photographs titled Memphis (c. 1972) and Gober's untitled sculpture of a bed (1988) distill private emotion with the same disinterested urgency,and so retrospectively open our eyes to a depth of feeling in the work of a photographer famous for his reserve.

- Evans often spoke of photography as a form of collecting, and in his pictures he collected signs of the times, past and present. Many of his subjects were quite literally signs, words and images that had been created to communicate. Cubism had introduced the shards of commercial culture into the realm of high art, and Minstrel Showbill (1936) and other Evans photographs readily recall Dadaist collage. The novelty of Evans's experiments in this vein lie partially in the fact that photography was often both the agent of transcribing the vernacular sign and, as subject matter, symbolically charged material in itself--for example, in

Penny Picture Display, Savannah (1936),

which is an homage to the unpretentious portraitist, a witty send-up of photography's talent for duplication, a taut modernist picture, and a pointed meditation on the contest between freedom and uniformity in American life. A diverse assembly of works by Frank, Friedlander, Gonzalez-Torres, Lichtenstein, Schmidt, Warhol, and Jacques Mahé de la Villeglé, among others, explores the persistent resonance of Evans's image world in art of the past halfcentury.

- Along with car culture and advertising, the movies play a prominent role in Evans's pictures of everyday culture--in

Torn Movie Poster (1930),

for example, or

Girl in Fulton Street, New York (1929),

whose subject emulates the flappers she has seen on the screen and in the magazines. Made by the few and consumed by the many, the commercial seductions of the movies are part of what we share and part of each of us--an enthralling American contradiction also engaged by Louis Faurer in an untitled photograph of 1938, by Hopper in New York Movie (1939), by Warhol in Gold Marilyn (1962), and by Sherman in Untitled Film Still #21 (1978).

- Before Evans there were already millions of architectural photographs in which the picture plane is parallel to the facade of the building. From this unexamined convention Evans abstracted a commanding, rigorous style. His photograph

Church of the Nazarene, Tennessee (1936)

suggests that he had learned from painters such as Piet Mondrian that the picture plane could constitute an ideal world unto itself. But Evans's frontal style was also a lucid vehicle of impersonal description. A photograph by Evans is both a bold pictorial invention and an uninflected worldly discovery--a fusion of opposites that is variously exploited in Ruscha's Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966), the Becher's Anonymous Sculpture (1970), and Gursky's Times Square, New York (1997).

- Evans's Subway Portraits of 1938-41 invite us to reconsider the rest of his work from an angle that might not otherwise come to mind. Made in the New York city subway with a concealed camera, the pictures are acutely specific portraits, but their serial uniformity evokes census-like anonymity. Evans addresses the subjects' deepest inner secrets, only to assert that they are incommunicable. His talent for evoking the psychology of individuals amidst others but nonetheless alone, in a world not of their making but nonetheless theirs, is echoed in the exhibition in works by Callahan, Adams, diCorcia, and Judith Joy Ross.

PUBLICATION

Walker Evans & Company Exhibition catalogue by Peter Galassi. 399 illustrations, including 67 in color and 332 in duotone, 272 pages, 10 1/2 x 11 1/2".

Walker Evans: Bridgeport, CT Photographs

Walker Evans American Photographs

This installation celebrates the 75th anniversary of the first one-person photography exhibition at MoMA, and the accompanying landmark publication that established the potential of the photographer’s book as an indivisible work of art. Together and separately, through these projects Walker Evans created a collective portrait of the Eastern United States during a decade of profound transformation—one that coincided with the flood of everyday images, both still and moving, from an expanding mass culture and the construction of a Modernist history of photography.

Comprising approximately 60 prints from the MoMA collection that were included in the 1938 book or exhibition, the installation maintains the bipartite organization of the originals: the first section portrays American society through images of its individuals and social contexts, while the second consists of photographs of American cultural artifacts—the architecture of Main streets, factory towns, rural churches, and wooden houses. The pictures provide neither a coherent narrative nor a singular meaning, but rather create connections through the repetition and interplay of pictorial structures and subject matter. The exhibition’s placement on the fourth floor of the Museum—between galleries featuring paintings by Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Jackson Pollock, and Andy Warhol—underscores the continuation of prewar avant-garde practices in America and the unique legacy of Evans’s explorations of signs and symbols, commercial culture and the vernacular.

Walker Evans, Roadside Stand Near Birmingham, 1936, photograph. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-DIG-fsa-8c52874

Walker Evans, American, 1903–1975. Interior Detail, West Virginia Coal Miner's House, 1935, Gelatin silver print, 8 7/8 x 7 3/16 in. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase.

Walker Evans, Negro Barber Shop Interior, Atlanta, 1936, photograph. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-DIG-fsa-8c52232

No comments:

Post a Comment