Thaddaeus Ropac

27 January—13 March 2024

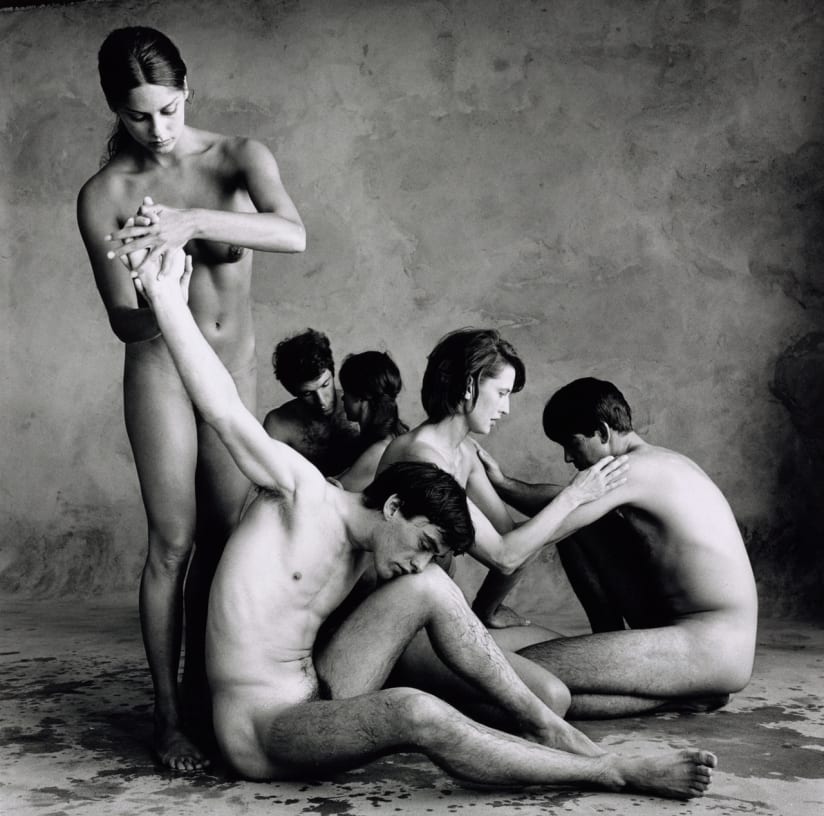

This exhibition is dedicated to a rarely-seen series of photographs by Irving Penn. Taken in 1967, the carefully composed images are the result of Penn’s collaboration with the Dancers’ Workshop of San Francisco, capturing the groundbreaking work of the American choreographer Anna Halprin. In addition to the photographic series, one of Irving Penn’s rare paintings is also part of the exhibition. Penn captured the dancers in his studio as they re-staged Halprin’s improvisational choreography, The Bath (1966). The group of 14 photographs, which were printed for the first time in 1995, highlight Halprin’s pioneering approach to movement and reveal a more experimental side to Penn’s practice. In its entirety, the series is exhibited for the first time in the German-speaking world. The summer of 1967 in San Francisco has become known as the ‘Summer of Love’. Young people converged on the city, drawn to its burgeoning counterculture that broke the taboos of American society, promoting community, altruism, mysticism and free love. Fascinated by the movement, Irving Penn travelled to the Bay Area the following September to document its participants with a series of group portraits to be published in Look magazine. He wanted, as he termed it, to ‘look into the faces of these new San Francisco people through a camera in a daylight studio, against a simple background, away from their own daily circumstances.’ At the heart of the avant-garde art scene in the 1960s was the Dancers’ Workshop of San Francisco. Their founder and choreographer, Anna Halprin, was a pioneer of postmodern dance. Her practice promoted healing and a sense of community through body awareness and improvised group interactions based on ritual, which radically changed modern dance.

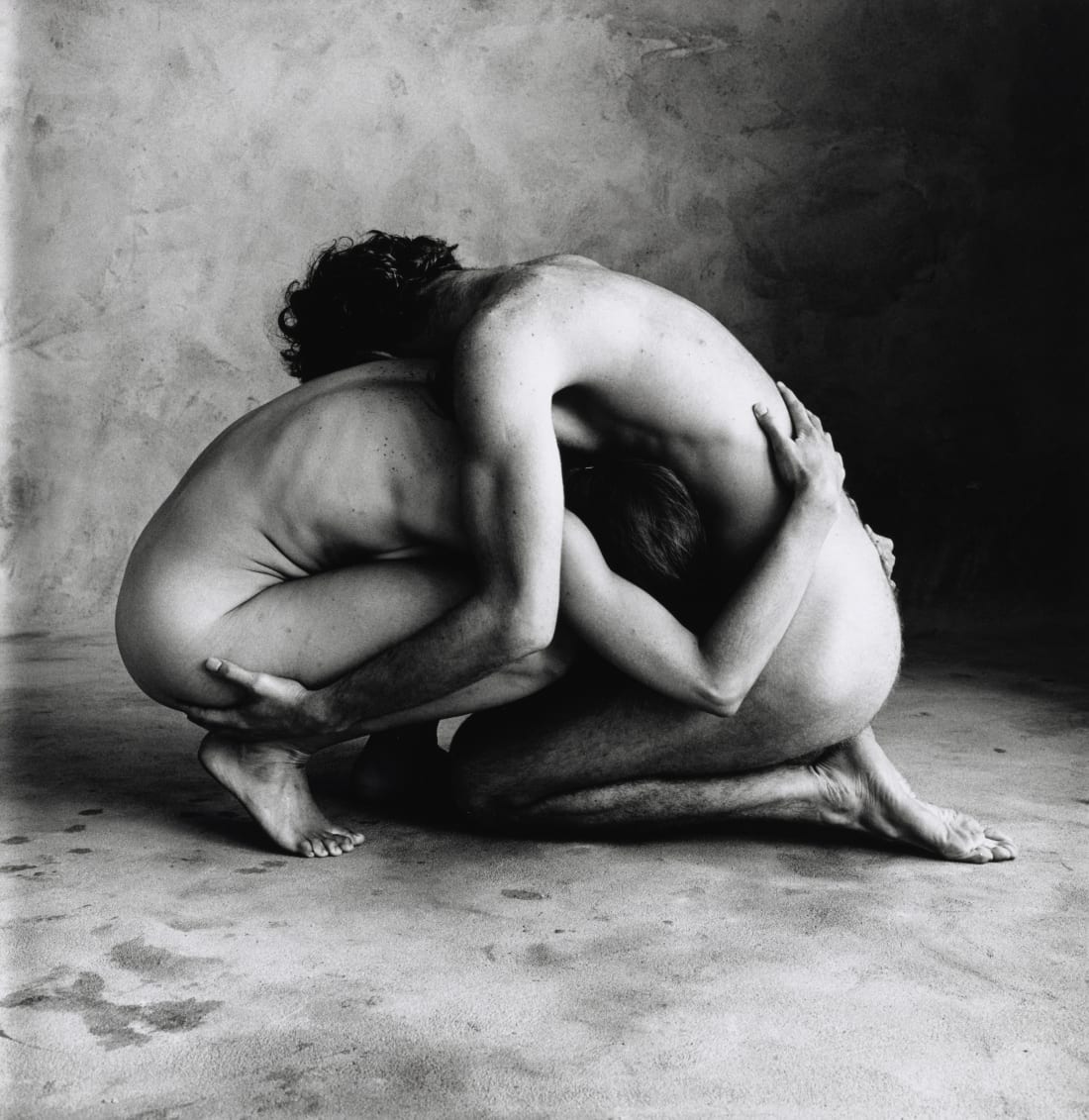

The Bath (G) (Dancers Workshop of San Francisco), San Francisco, 1967

Gelatin silver print, print made 1995

38.6 x 37.8 cm (15.2 x 14.88 in)

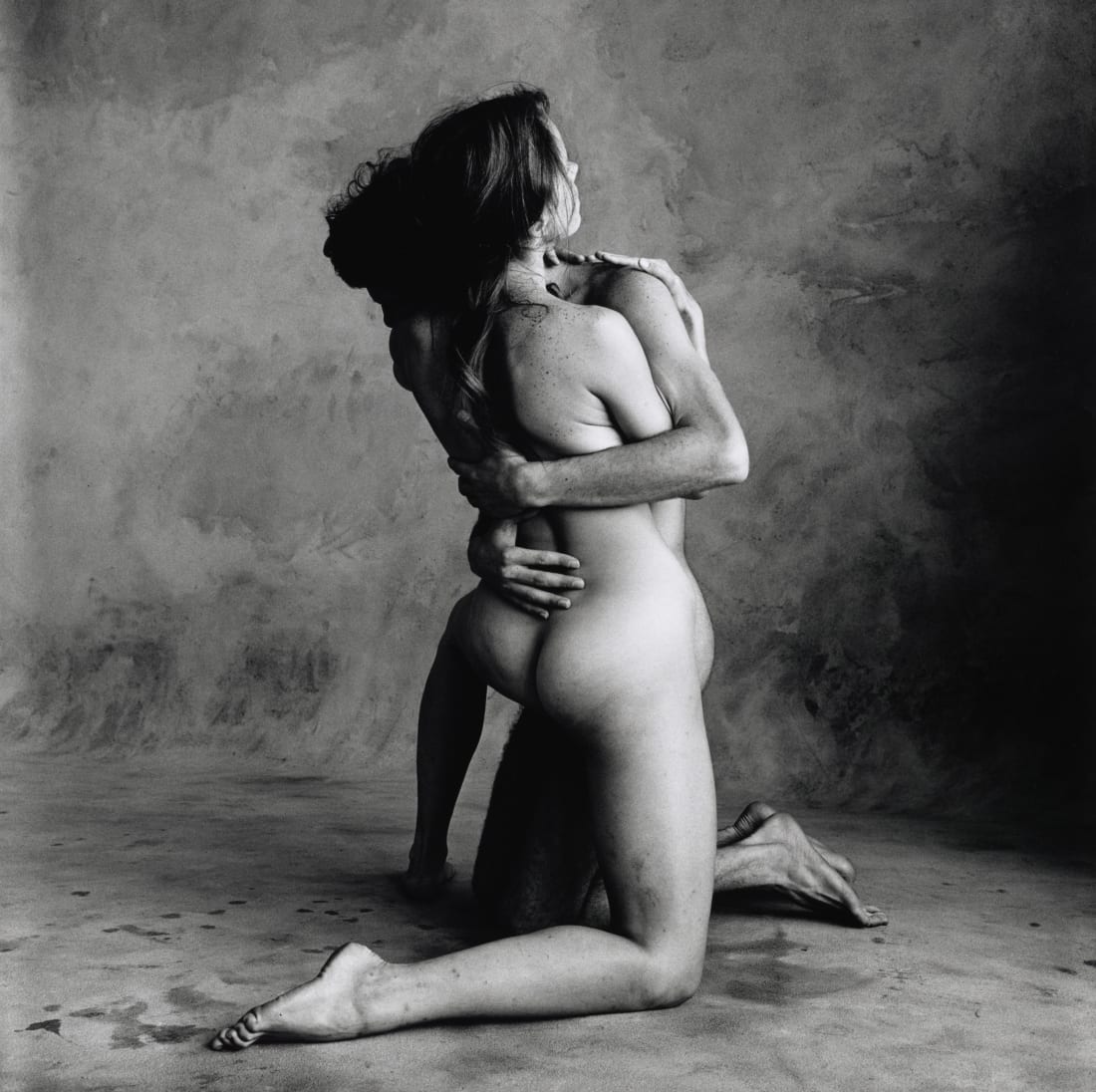

The Bath (H) (Dancers Workshop of San Francisco), San Francisco, 1967

Gelatin silver print, print made 1995

38.9 x 39.1 cm (15.31 x 15.39 in)

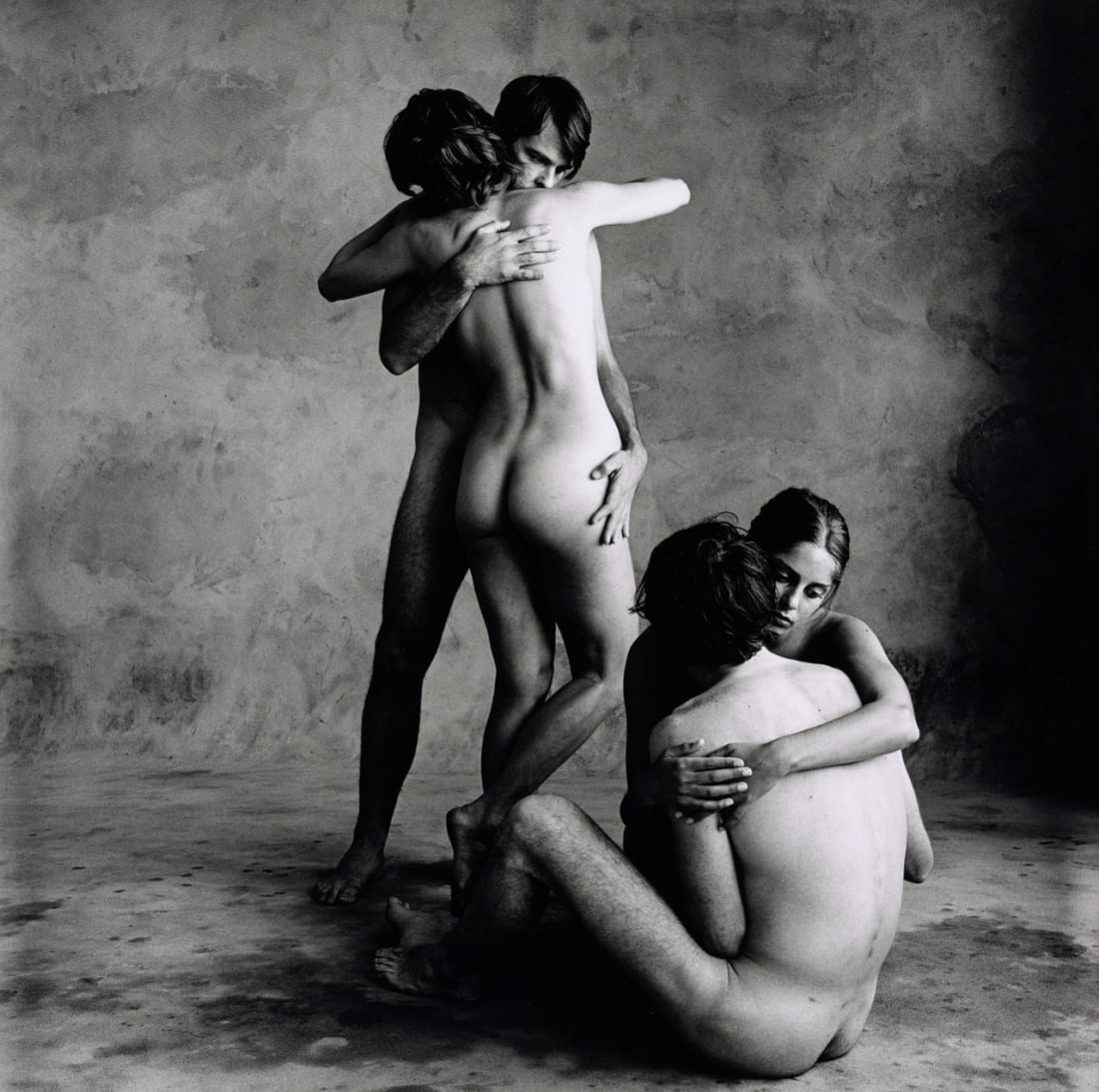

The Bath (L) (Dancers Workshop of San Francisco), San Francisco, 1967

Gelatin silver print, print made 1995

39.1 x 39.1 cm (15.39 x 15.39 in)

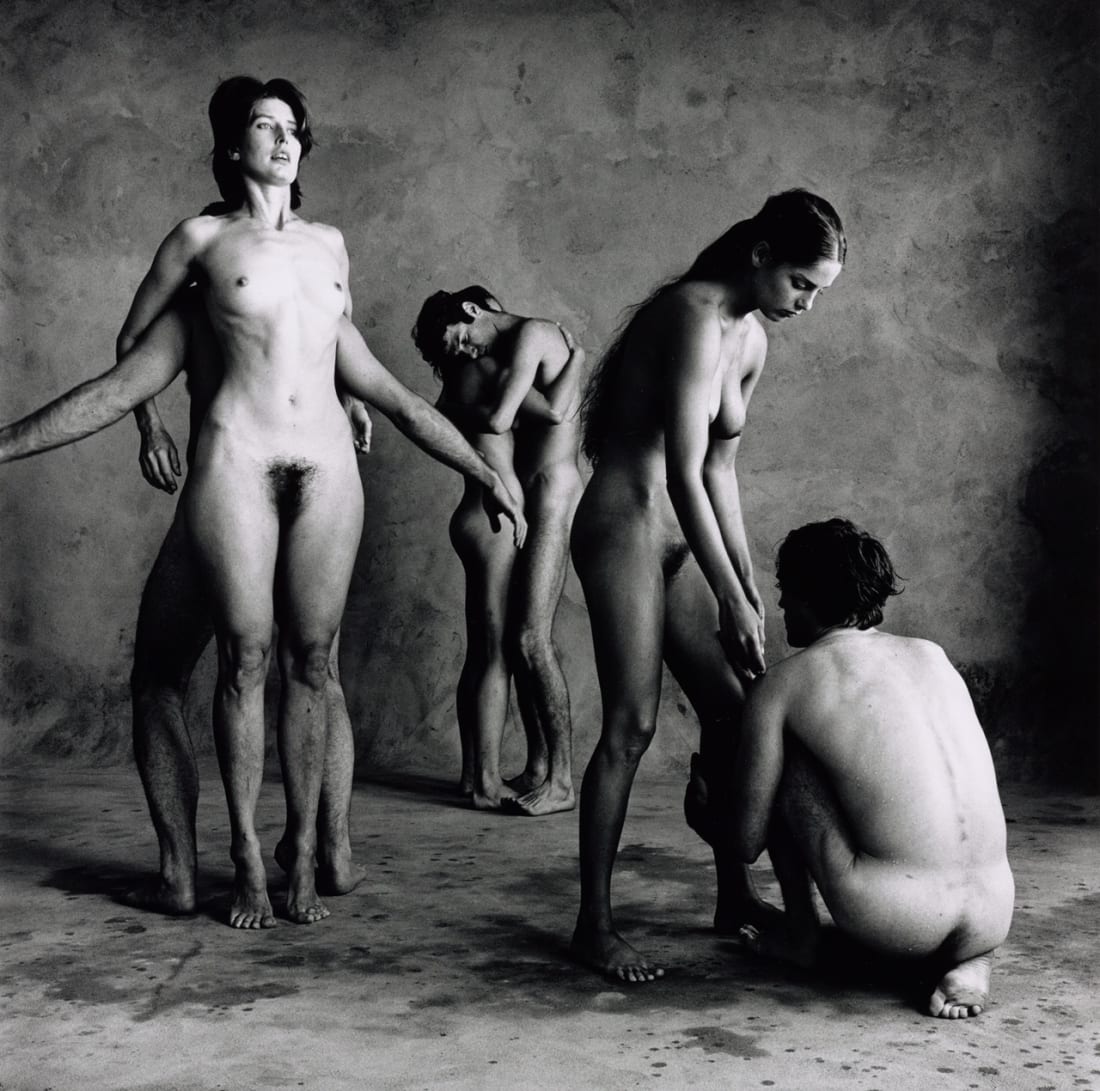

The Bath (M) (Dancers Workshop of San Francisco), San Francisco, 1967

Gelatin silver print, print made 1995

Dance is breath made visible,’ Halprin said of her approach. Her daring performances were often participatory and rarely took place in traditional stage settings, with one instance leading to a summons for indecent exposure only a few short months before Irving Penn photographed the troupe. In the original performances of The Bath, the nude dancers bathed each other in fountains or using jugs and buckets of water. ‘The performance of the simple action,’ writes Halprin in her notes on The Bath, ‘the natural action, objectifies what is really going on inside the performer’s self.’ Penn omits the containers in his photographs, although fine droplets of water appear here and there on the dancers’ skin, and wet patches remain on the studio floor. When Halprin saw the pictures, she observed that Penn’s compositions put forward ‘the absolute purity of a boy and girl relating to each other in the most magical way, and yet it seemed real. What [the dancers] were left with was creating the essence of the bath, but it had nothing to do with actual bathing anymore.’ Although the majority of the dancers remain unnamed, Halprin’s daughter Daria Halprin can be identified throughout the photographs, her powerful gaze highlighted by Penn in one of the series’ most arresting images. Coming in laterally from the window on the north side of the studio, the daylight wraps itself around the dancers’ bodies as they interlace. ‘The pictures are primarily of embraces,’ Penn remarked upon rediscovering the photographs in 1995, ‘beautiful and touching. Here they are without clothes, there’s love, the gestures are tenderly erotic but certainly not pornographic.’

And yet the photographs were considered too daring to be published in ‘The Incredibles’ essay featured in the 9 January 1968 issue of Look magazine. According to Vasilios Zatse, deputy director of the Irving Penn Foundation, they remained forgotten for almost three decades until Halprin contacted Penn in 1995, enquiring about the photographs for her archive. He selected 14 negatives and printed them for her, using the gelatin silver process. Although the two never met, Penn stated at the time: ‘I didn’t know Ann[a] Halprin at all, but I know from these pictures, I tell you, I like her very much.’ Dance was a recurring theme throughout Penn’s career. From his photographs of American ballet companies in 1946 to his 1999 series capturing the movements of dancer and choreographer Alexandra Beller, the artist maintained an interest in new and avant-garde forms of performance. It is undoubtedly thanks to his affinity for the art form that Penn was able to capture The Bath with such acuteness. Where Halprin found that the photographs brought out the essence of her own work, Penn remarked that they gave him a sense of ‘serenity,’ which he was, in his words, ‘not used to.’ The series, therefore, represents a unique confluence between modern photography and postmodern dance and constitutes a rare document of the meeting of two artistic minds. Irving Penn, Untitled, 1987. Ink, watercolor, and dry pigment with gum arabic over platinum-palladium print on paper. 59.7 x 48.9 cm (23.5 x 19.25 in) Irving Penn, The Bath (G) (Dancers’ Workshop of San Francisco), 1967. Gelatin silver print, print made 1995. 38.6 x 37.8 cm (15.2 x 14.88 in) In addition to the photographs, the exhibition presents a work on paper from 1987 that highlights the broad spectrum of Irving Penn’s artistic practice. After his retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1984, the artist returned to the medium of painting and, inspired by his experience with printing photographs, developed an experimental technique: he photographed drawings and enlarged them as platinum-palladium prints. He then used the resulting prints as a painting surface, which he worked on with a combination of watercolours, ink, dry pigments and gum arabic – materials that lend the works a complex surface structure. The photographic series The Bath relates to Irving Penn’s wider interest in exploring movement and organic forms, a theme that can also be found in his abstract painting; the entwining shapes recall the interlacing bodies of the dancers.4 Born in 1917 to immigrant parents in Plainfield, New Jersey, Irving Penn attended the Pennsylvania Museum School of Industrial Arts from 1934—38 and studied with Alexey Brodovitch in his Design Laboratory. His first photographic cover for Vogue magazine appeared in October 1943 and he would continue to work at the magazine throughout his career. In the 1950s, he founded his own studio in New York and began taking advertising photographs alongside his private, experimental work. In the early 1970s, Penn closed his Manhattan studio and immersed himself in platinumpalladium printing in the laboratory he had constructed on the family farm on Long Island. There he created his innovative Cigarettes series, which was shown in his first exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1975, as well as his Street Material series, shown at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York in 1977. The first retrospective of Penn’s work was organised by The Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1984 and toured internationally to countries including Japan, France, Spain, Germany, Sweden, Israel, Italy and the UK. He donated his archives to the Art Institute Chicago in 1995, and established The Irving Penn Foundation in 2005 to promote knowledge and understanding of his artistic legacy, including the diversity of techniques, mediums and subject matter that he explored.

Recent exhibitions of the artist’s work include Irving Penn: Beyond Beauty at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. (2015), Centennial at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2017), which travelled to the RMN - Grand Palais, Paris; C/O Berlin and the Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo and Irving Penn, Chefs d’œuvre de la collection de la MEP at the Franciscaines in Deauville (2023). From March 2024, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco will present the celebrated Centennial-retrospective, including 196 photographs, spanning every period of Penn’s nearly 70-year career.

Recent exhibitions of the artist’s work include Irving Penn: Beyond Beauty at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. (2015), Centennial at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2017), which travelled to the RMN - Grand Palais, Paris; C/O Berlin and the Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo and Irving Penn, Chefs d’œuvre de la collection de la MEP at the Franciscaines in Deauville (2023). From March 2024, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco will present the celebrated Centennial-retrospective, including 196 photographs, spanning every period of Penn’s nearly 70-year career.

No comments:

Post a Comment